Trauma-informed, injuries monitored. Beyond safety and risk with new paradigms

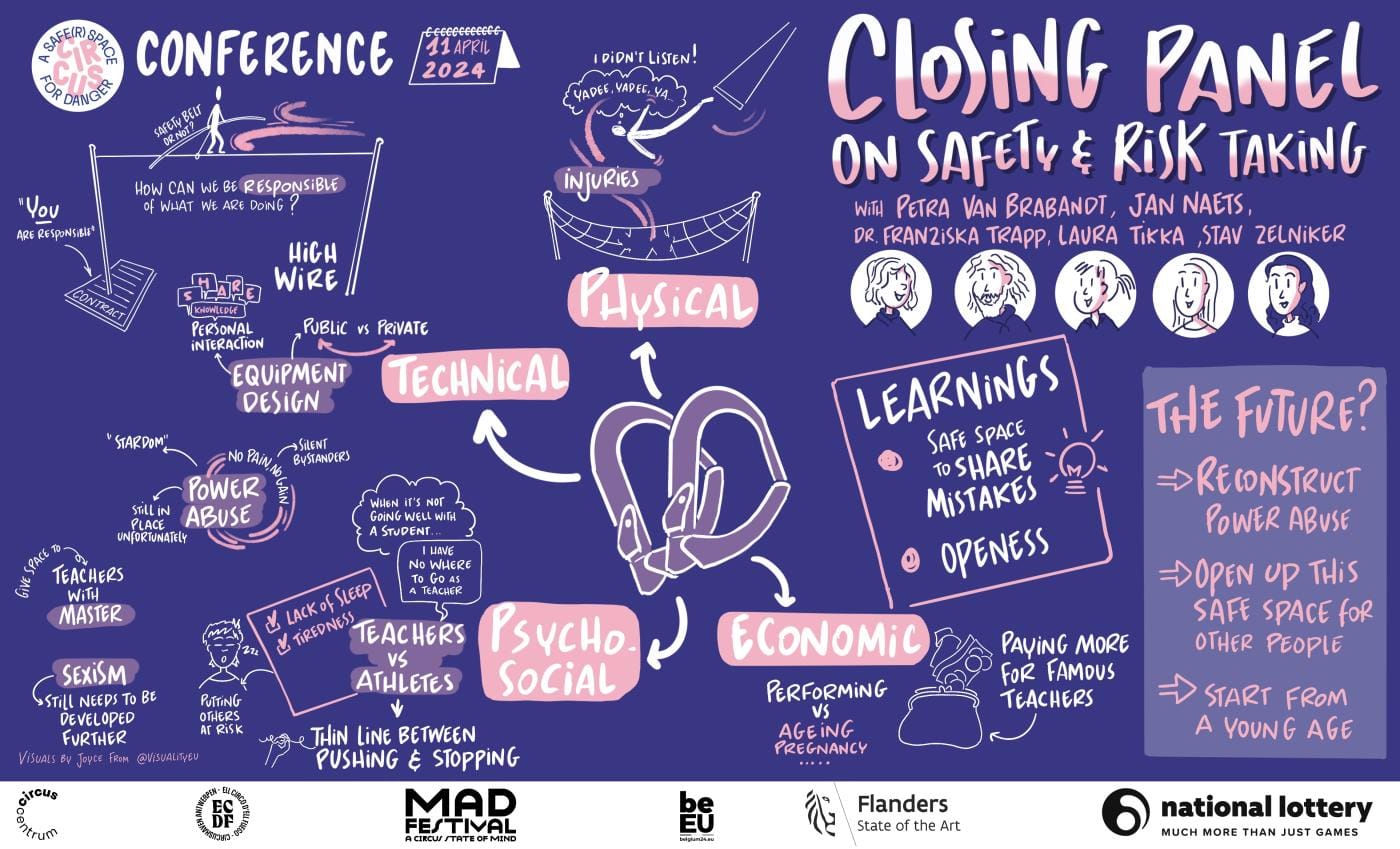

What is the common denominator of a sense of safety from a young professional's eye in the circus sector, and what is important to underline or still missing from reflections on risk? And what about enlarging the spectrum, including the sociological element of safety beyond the circus bubble? During the conference Circus - a safe(r) space for danger by Circuscentrum, Ell Circo D’ell Fuego and MAD Festival, I attended two workshops exploring safety from a holistic perspective. In this text, I recap my experience as a participant in Mieke Gielen's workshop Trauma-informed Approach and Monitoring the health and wellbeing of circus artists by Marion Cossin (CRITAC) and Janine Stubbe (CODARTS). The closing panel of the second day of the conference, On safety and risk-taking, moderated by Petra van Brabrandt with Stav Zelniker, Laura Tikka, Jan Naets, and Dr. Franziska Trapp as guests ended the day, summarising the topic from a collective viewpoint while honouring the complexities. Some points have been made as an introduction to each paragraph, to highlight the perspectives we came to through each collective experience, thus motivating and inspiring the flow of thoughts around every aspect of this article. Get comfy and be receptive!

Before diving into the mentioned topics, it is also essential to underline the great care of each session's introduction by the responsible organisations involved in the conference. Every day the team set up the guidelines of the event, introducing the figure of the care angels, spread around the workshops and the welcome points, always available for any questions or concerns. The participants are invited to remind us that all of us here together are responsible for the quality of the human experience, through giving consent, respecting each other and the confidentiality of what could be shared, listening without interrupting or judging, and speaking without monopolising the floor.

Towards a trauma-informed society

By understanding what trauma means, how it confuses the stress responses, and how to deal with trauma-triggered stress responses in a supportive way, teachers could share the knowledge and pave the way towards a trauma-informed society.

Mieke Gielen co-leads the pedagogical coordination of Ell Circo D’ell Fuego, teaches all ages and levels and is involved in the development of TaRMaK, a circus program to empower children and teens facing intrafamily violence. TaRMak focuses on creating positive and fun experiences for children and teens while also working on strengthening and supporting them in the background. This core function represents one of the key goals of this workshop, which introduced a trauma-informed approach for educators and facilitators working with children, (though it applies to adults too). Mieke invited us to do a small exercise. Each of us received a yellow balloon, which we blew up and held between the palms of our hands. She then asked us to close our eyes and focus on a text that she would read, letting us know that she was holding a needle that she would use to pop any of our balloons at some moment during the narration of the text. The knowledge that Mieke was walking between us, holding a needle that could pop our balloon, made everyone stressed and attentive to listen to her steps in the room. This state of alertness made our attention shift to the balloon and made it impossible to listen to the narration of the text, which seemed without any purpose on its own.

When asked to describe the experience, some said they held the balloon tighter if they heard her footsteps nearby, while some admitted they could not keep their eyes closed. Another person confessed that they indeed had a fear or uneasiness with balloons since a young age, which caused an urge to refuse to do the exercise or leave the room altogether. Symbolically, a person said they felt like going from the feeling “it's dangerous’’ to “it is okay’’ and back. This challenging exercise proves that a body can react fast to a stress stimulus that does not necessarily come logically as part of a thought process since the body becomes aware of a trigger. At the same time, a coping mechanism can appear reassuring, such as focusing on the calm tone of voice of the narration, no matter what it is about.

It does provide a nice link to what being trauma-informed means: to always take into account that everyone can have profound experiences which can cause their stress system to be confused. The trauma-informed approach changes from “What’s wrong with you?’’ to “What happened to you?’’, which shows that a switch of attitude can make a relevant change to the support given to a person under stress. A person under stress can be described as being outside of their window of tolerance, the zone in which someone can cope with stress. As long as the stress stays within the window frame, the person can function normally, contrary to situations of stress that can trigger a Fight, Flight, or Freeze reaction instinctively, as we saw with the balloon exercise. When the stress level is outside of the window or lasts longer, especially in the case of children, this can lead to situations that could cause trauma. A trauma can come from a serious one-off incident or a continuous unsafe situation, such as neglect or abuse. Chronic or ongoing stress can deregulate the stress system, leading the child to be in a constant state of alertness. As a result, the window shrinks, making the child more easily triggered even by seemingly harmless situations.

An adult can help the child recognise emotions, express them, and calm down, thus making the ‘window’ expand. For educators, the importance lies in being able to support a child who could be coming from a rough family background. What should be underlined, especially for children and teens, is that the triggers might be countless and hidden in their subconscious, thus bringing them into a state of constant alertness, which impacts their ability to be aware of their sensations, relax, have fun, and learn. At this point, the multiple benefits of circus education became the focus. While there have been six researched methods to heal trauma without medication (yoga, theatre and movement, therapy, EMDR, neural feedback and psychedelics), circus is not included yet, even if it brings a lot of benefits such as physical exercise, play, belonging, success and self-confidence.

Three R’s are proposed, replacing the three F’s of the stress responses - Fight, Flight, and Freeze - as methods to recognise, address, and support. Firstly, it is necessary to Regulate by helping the person calm down and keeping in mind that their behaviour is not a choice. Secondly, Relate by starting to make contact with the person, little by little, since building a relationship takes time and trust. Thirdly, the Reason. Supporting the person in reflecting and learning from this experience. Seemingly small steps can be challenging for them. The final R is to Remember self-care: eat well, sleep enough hours, and include fun and play in your practice. As a participant of the workshop remarked, sometimes what is needed is a daring space, not a safe space, a space in which you can be a little bit out of balance, a little bit out of your comfort zone, to learn valuable lessons and be honest, first of all to yourself.

Trauma-informed approach - Presentation

Monitoring: Vital, but tricky

The most important element when monitoring the health and well-being of circus artists is to create a safe environment of trust where confidentiality is preserved.

After lunch, my exploration of safety continued with the second workshop of the day, Monitoring the health and wellbeing of circus artists led by Janine Stubbe, a human movement scientist employed as a professor of Performing Arts Medicine at CODARTS Rotterdam, and Marion Cossin, an engineer of research in circus arts at CRITAC - Centre for Circus Arts Research, Innovation and Knowledge Transfer, an independent organisation but located in the Montreal National Circus School.

Janine introduced the CODARTS tests in place for monitoring the health and wellbeing of its students. The professional circus school has a whole educational programme on health and a monitoring system. However, as Janine admitted, knowledge and data on circus artists are still scarce due to the infancy of the department and the large variety of the disciplines. CODARTS implemented a system called TATA, a Team Around The Artist. It includes scientists, dieticians, psychologists, physiotherapists, artistic managers, teachers, and a health coach connected by several monthly meetings. Additionally, students get free health support and a whole health educational programme. Then, there is a research team of movement, data, music and dance scientists and a software engineer to prevent injuries and mental health problems.

As Janine highlighted, before designing an intervention for an injury, they need to know the number of injuries in place and their characteristics (back, shoulder, ankle - acute or old injury, etc). Then, it is necessary to assess the risk factors by doing screenings on the students, such as physical tests, sports medical and physiotherapeutic screenings, and an intake questionnaire (previous injuries, surgeries, etc). Screenings are vital preventive methods before interventions, and it is relevant to collect all the risk factors contributing to sustaining injuries.

When she started 10 years ago, there were no monitoring tools specifically for the professional schools' circus sector. For that reason, they developed the Performing Artist and Athlete Monitoring Tool (PAHM), in which over 2000 artists and athletes participate worldwide. With this tool, they can collect the data, and analyse and visualise the results. One interesting element is that, often the recording of an injury is done when a student is no longer able to perform, which is already too late. At that point, it is only possible to see the tip of the iceberg. To prevent it, it is important to see below the surface of the water. So, when talking about health problems, they refer to any complaint, pain, or stress that the student might have, irrespective of a possible decrease in performance and a risk of sustaining an injury.

According to a prospective cohort study on injuries and health problems among circus artist students in the Netherlands, the results of all health problems throughout one academic year show that 71% were injuries, 21% were illnesses, 5% were mental health problems, and 3% categorised as ‘’other’’. Additionally, the students appear stronger at the start of the academic year and suffer an injury during the periods before competitions and performances, such as January and February. Regarding injuries, it is interesting to note that circus is hard to study and monitor compared to dance because of the great diversity of its disciplines. In aerials, the shoulders are the most common area of injury, while in ground acrobatics, it might be the lower back, the wrist or the ankles. That’s why there is not yet a specific circus test, as they are still developing adaptive screenings for physical and mental health.

According to their data, 1 out of 3 students had a muscle injury, and they suspected that having a vegetarian or vegan diet could potentially be a risk factor. At that point, they measured the correlation between protein intake and injuries. While not exhaustive, what they found out was an indication that students taking the majority of their protein from plants are probably more likely to suffer from more muscle injuries.

PEARL next stage research lab Codarts - Presentation

Next up, it was Marion Cossin who introduced CRITAC. Their work follows four innovation axes: The monitoring of human performance, the designing of environment and equipment, the work on digital technology in systems monitoring the health of artists, and lastly, social innovation, meaning talking about social issues raised through art. CRITAC is promoting a collective working model in which everyone works together, even if they can have multiple projects running simultaneously. One example that Marion mentioned is using biomechanics and technology to improve circus equipment and help circus artists. For example, the design of a symmetrical Russian bar wants to protect the bases and assist the lower back, with support for both shoulders. However, a tricky issue coming up often in their projects is that they need to be backed by numbers. Marion emphasised the challenge of monitoring the health of artists in the circus sector, due to it involving high risk not just physically but economically as well, in an environment that demands high-performance levels, mastering multiple disciplines, elite level of technique, as well as finding and portraying a unique artistic identity.

On average, Marion said, injuries are about 10 per 1000 times of exposure, although there is no mutual international agreement on what is an injury and what counts as an exposure. Is it one hour of training, one training session, or one performance? Furthermore, the performance or training context can differ, as does the method of each teacher and school environment, which makes it hard to standardise measuring procedures. Unfortunately, there has still been limited research on mental health issues, apart from self-reporting of symptoms.

CRITAC is dividing risk factors into three main categories. The first being artist-related intrinsic factors (background, lifestyle, movement quality, technique, etc.), followed by the external factors (schedule, social support, equipment, etc.), and finally the preventive strategies (safety, preparation, load management). However, assessing the risk factors does not necessarily mean that injuries can always be prevented.

Additionally, CRITAC is conducting work on various projects and papers, such as measuring the sleep and fatigue of students, their body composition (symmetry and proportionality) and physiological adaptation during the academic year, giving recommendations to the teachers based on the results of each research project. Other tests relate to psychological measurements in the form of questionnaires sent to students about anxiety, fatigue, and day-to-day challenges. A recent piece of research not yet published is a statistical tool to evaluate the risk factors in relation to risk aversion, taking more variables into account. They have also looked into measuring the workload of circus artists, intending to see if the metrics from sports are relevant for them too.

Last but not least, Marion mentioned some recommendations that have come out of their work on measuring the health of circus artists. Firstly, the environment, whether that's a circus school or company context can play a significant role. The objective and scope of a research project must be clear since some methods or calculations are not feasible. Of course, a multi-disciplinary team is necessary, and ethical considerations such as consent, confidentiality of information and non-intrusive or minimally intrusive methods are needed. Ending her section of the workshop, Marion underlined that their next steps could be working more across sectors and disciplines, improving the surveillance systems for injuries and going deeper with technological innovation for this goal.

Strive for technique or preserve happiness?

What is needed to improve safety? Deconstructing the power abuse system. Overcome past stereotypes. Foster the idea of being able to learn something in a million ways instead of following one rigid method. Create safe spaces open to more people. Educate the new generations with new patterns for a new normality.

Some of the points not addressed in the previous workshops were then brought into discussion in the closing panel of the second day, On safety and risk-taking, moderated by Petra van Brabrandt, a philosopher and head of research at Sint Lucas Antwerp - School of Arts KdG and a teacher of semiotics, cultural criticism and artistic research. In this last panel, we confront safety from various standpoints, represented by the four guest speakers, Stav Zelniker, Laura Tikka, Jan Naets, and Dr. Franziska Trapp. Stav Zelniker would bring the perspective of a professional circus artist and former student from Carampa, FLIC, and ESAC. Laura Tikka was a circus artist for many years, but she would speak from her current role as a circus educator with an MA in educational sciences. Then, Jan Naets would bring the perspective of a technician of more than 20 years with different companies and as technical manager and co-artistic director of Basinga, a highwire French circus company. Lastly, Dr. Franziska Trapp, a postdoctoral researcher at the Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium, would be invited to speak about her research on safety issues around equipment design.

In her introduction, Petra van Brabrandt remarked that perhaps we are speaking less about institutional safety, regarding all the regulations, laws, and charges made up to guarantee safe environments, not only financially, but in terms of safety, from power abuse, harassment and transgressive behaviours and all kinds of discrimination. A relevant topic indeed, considering a lot of surfacing testimonies and complaints about circus education, which, simultaneously raises the question of how to create environments that are apt for learning.

Following a first round of introductions of each speaker's point of view on risk, Petra directed a question to Jan about the ambiguity regarding safety and risk-taking, between audiences and professionals or in institutional contexts. The current procedure is to write everything down in contracts. Jan responded with the word liability and underlined the difficulty of going from theory to practise within communication between a festival and visiting artists. Consequently, more and more paperwork is required, but quality standards still need to be met. If not, this allows the artists to say no to a performance. He then mentioned an interesting French law: If the circus performer’s body does not leave the apparatus then no safety net is necessary.

Saying no, however, requires assessing your mental strength and trusting the process. To this point, Laura noted that while physical safety at a basic level is understood quite well by students, mental tiredness is often underestimated. Coupled with a lack of rest and malnutrition, it can increase the risks for everyone involved, not just the people on stage. These habits, together with not listening to advice from doctors and physios, were Stav’s biggest mistakes, which contributed to many of the injuries she sustained during her studies. She admitted that when she returned to the school, she was more supported but was feeling pressure to be there, to do better, to get back to it, to continue. For Laura, it is easier to be a teacher with younger students since they come for their pleasure, and their parents are responsible for them.

On the contrary, for grown-ups, the circus school has no right to contact anybody, including parents or social workers, especially if the student is foreign. As a result, the strategies and possibilities of the teacher are much more limited. Unfortunately, there is often the case that an artist might work even if being ill just because they have to be on stage. Contrary to this, there are more supportive measures for paying an artist, even if physical health should be more regulated instead of representing an exception. Franziska added that awareness needs to continue to be built not simply as knowledge about the apparatus, but as the development of the whole art form through the coming together of communities.

Is having a psychotherapist as part of the team standard in companies? Jan replied that for Basinga, it is usually not the case. On the same train of thought, what happens when dealing with pregnancy, illness, and ageing? Petra asked Franziska how to address ageism, ableism, sexism, transphobia, and racism in circus work and how to communicate them to the receiving audiences. Franziska’s response contained an unpleasant truth about the circus world, being a white-dominated space. Very often, what the majority of the sector preaches does not usually correspond with what is being done.

Then, it was time to address all the testimonies that have come out about the endemic presence of power abuse in circus education and the educational practices of no pain, no gain. To this topic, Laura confessed she does not have an optimistic but realistic view. One positive development is the requirement from schools for teachers to have followed at least a pedagogical course. She then addressed the need to move past stereotypes, such as "You are a man, you should be able to lift that girl’’ and “You should be thankful you got into the school, so do whatever is necessary to finish.” To her, pedagogy is different from being an educator, because someone with a pedagogical background can recognise what it is to be a student and recognise, assimilate, and accommodate others accordingly. Stav agreed to this point and added that power abuse still exists, and there is a fine line between over-pushing past limits on the one hand and accompanying someone to reach their top form on the other hand.

Accordingly, this led Petra to question the implications for an artist' CV if they complain about an abusive teacher, especially if the teacher is considered an expert in their discipline and cannot be replaced. Stav posed an interesting dilemma: what do we need? To be happier or more skilled? She responded it is always choosing the latter, that there is not just one way to do and learn things, and by opening the mind, possibilities and solutions can appear.

Petra concluded the panel by observing the speakers expressing pessimistic thoughts through an optimistic phrasing. What is needed to improve safety? Laura brought up the idea of deconstructing systemic abuse of power by fostering the idea of being able to learn something a million ways instead of following one master. Franziska underlined the necessity of creating real safe spaces that are open to more people, rather than perceived ones that reproduce exclusion. Jan remarked that the conference' attempted approach was the need to share among practitioners and with the new generations so that they could become the new normality.

When asked about learnings and takeaways from the days of the conference, the speakers discussed circus being a mirror of society and the necessity of safe spaces to share mistakes and learn from each other. The underlining atmosphere of the whole experience created intimacy between participants, fostering respect, openness, and kindness.