Entanglements, Kinship, Clown and Politics

A conversation with Laura Murphy and Nicole A’Court Stuart

[by Elena Stanciu and Valentina Barone]

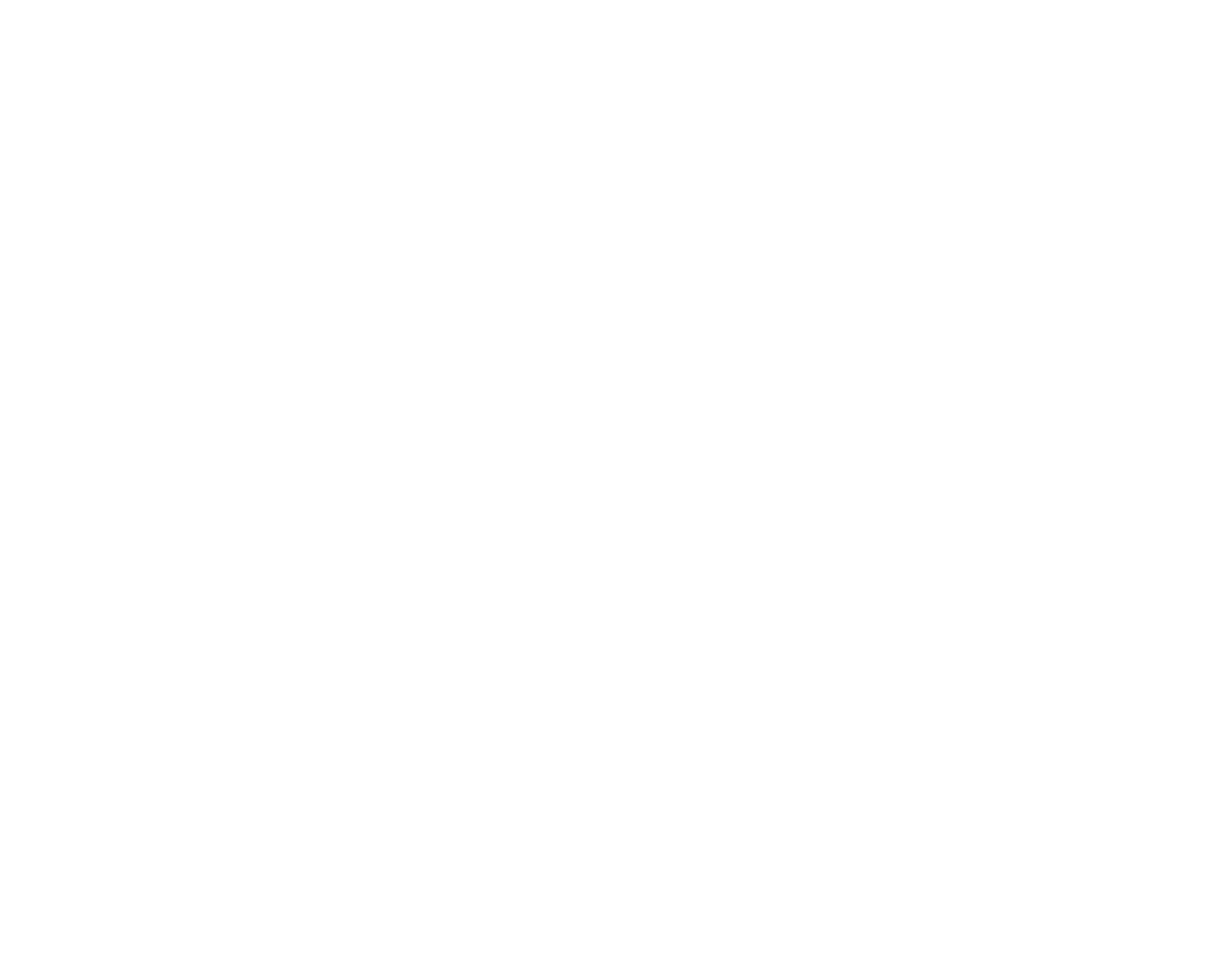

Blending clown, performance art, spoken word, autobiographical storytelling and aerial acrobatics, Laura Murphy (Contra Productions) creates work that simultaneously interrupts, disarms, provokes, and stimulates critique. In the two productions from the company - Contra (2019) and A Spectacle of Herself (2023), questions around body politics, queer identity, female sexuality, control, and power take centre stage. The two solo performances are often described as genre-defying. Yet, Laura’s oeuvre can be seen as defining a particular approach to performance art, in which notions of voice, presence, and representation are weaved, to articulate and deliver sharp critical work.

Whereas the work bears heavy personal tonality, with Laura’s signature staging of a plurality of dimensions tightly connected to their person (body, voice, personal stories), the process of creation involves an array of relationships, connections, contributions, and exchanges. In a talk facilitated by Circuscentrum for SMELLS LIKE CIRCUS 2024, with Laura and Nicole A’Court Stuart - Creative Producer at Contra Productions - we hear more about this process, the artistic collaboration with Ursula Martinez (Director of both Contra and A Spectacle of Herself), and the creative entanglements that traverse their work, all anything but a solo effort.

As Laura and Nicole describe a unique type of kinship in their collaboration, we come to think of notions of entanglement, connection, and partnership as terms of the zeitgeist, albeit challenged by broader politics of disconnection and individualism. We started this talk with a declared interest in the autobiographical dimensions of Laura’s work, and we ended with a deeper understanding of the plurality of biographies that converge to bring the work about. Indeed, a response to patriarchal hierarchies and models that no longer serve us may be found in embracing new methodologies, new ways of co-creating and co-existing, creative and collective entanglements, as alternatives to modernity’s individualistic preferences. Laura, Nicole, and Ursula have created performances and methodologies, hybrid entities where performativity affect and criticality operate conjointly.

This strong meta-perspective on deconstructing obsolete work models is matched by the politically engaged and high-stakes work that is put on stage. Humour, contemporary clowning, subverting and recontextualising the voices of patriarchy (quite directly, through lip-sync), all constitute a critical repertoire that traverses both Contra and A Spectacle of Herself. We are reminded of Audre Lorde’s dictum, according to which “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” as we reflect on what Laura Murphy’s tools aim and manage to do. Rather than aiming to dismantle the “master’s house,” can the work be seen to offer more concrete deconstructive approaches, and aim for the “master’s tools?” We think - yes! The female body (or body identified as female) on stage, nudity, the question of taking space, sexuality, representations of mental health issues – these are all “tools” reappropriated in the work of Laura and Nicole.

Elena Stanciu: Can you describe your professional relationship and how you operate your company today?

Nicole A'Court-Stuart: We've worked together in various ways for a long time and we've been friends for a really long time as well. We started collaborating when Laura was applying for her first lot of funding for the development of Contra. I had quite a traditional producer role, in that particular context, but soon I started being more involved with the creation space and artistic choices being made. Because we are so close, we also share a certain language, and we really understand each other, which is why we don't have very traditional boundaries between our roles in our company; we're a little bit fluid. When the pandemic hit, we started thinking about how to continue the work, and what kind of aesthetic interests we had - it led us to ask what film could allow. We started working on a publication and we started making a research film, which led to A Spectacle of Herself.

I think that was the beginning of us standing together in front of something, because we’re usually in a different setting, where Laura’s on stage and I’m not, and where my role is carrying a sort of dialogue, translating the work together with people who are off stage with me, for instance with Ursula (red. Director of A Spectacle of Herself). While finishing the film, I stepped into doing visual direction. I think that defined our very collaborative work structure now. It’s tricky to talk about it as a collaborative process because Laura is often still centred as a solo practitioner, and that creates a certain idea of how the work is carried out.

Laura Murphy: I agree! In the making of both Contra and A Spectacle of Herself, my relationship with Nicole and Ursula was really central. It feels strange saying “written and performed by Laura Murphy.” Yes, it is me on stage and those are my words, but so much of those words come from playful times with Nicole or Ursula, or from a conversation we've had. Solo work is appealing to watch, partly because it feels that the artist just landed on stage and is spilling their guts. The reality is that it is a product in the same way that circus is, or any other physical discipline.

Valentina Barone: So there is a merging between the personal and the collective somehow? What’s at the root of your connection?

Laura Murphy: Yes. Nicole and I are interested in this connection between the personal, the everyday, the mundane, and the political. I see this as a theme carrying on through our work. I completely see that beginning to direct as a team is shaping our collaborative practice.

Nicole A'Court-Stuart: I think something that we share in common, and also with Ursula, is that all three of us are neurodivergent, in different ways. For me pattern recognition is a strong tool, I see what we create as a code. It's a bit abstract, but it allows us to approach the very personal work in a functional way. We look at material that’s incredibly personal and place it in a broader thematic spectrum, following codes and patterns, and anchor it in what’s important and what matters.

Valentina Barone: Are there any limitations to working with someone who is also privately close to you?

Nicole A'Court-Stuart: I think us three [red. Nicole, Laura, Ursula] sharing a creation language, so to speak, sets up a particular space, which is not always immediately accessible, when someone joins in from the outside. It can appear informal, and chaotic, so sometimes we have to step back into more normative structures, especially towards the end of production. It's a different way of working, and I think it’s because we come from circus that we allow the process to have some element of disruption.

Elena Stanciu: In recent years we focus a lot more on care-taking in artistic processes and the spaces we design. Do you have this sort of active affirmation and awareness of introducing different work models, in creation or in how you tour?

Laura Rosemary Murphy: Most often it’s me, Nicole, and Ursula in the room, and that creates a special type of openness and safety. But we are looking at a new project, in which we would bring other people in to perform, which means we have to make sure we make conscious decisions about how we work.

Nicole A'Court-Stuart: It’s important to recognise that other people we bring into our company aren't our family in the same way, even if we are close. We need a much more professional space, to formalise things, have more check-ins, but also offer alternatives to the way theatres work technically–often very long hours, oppressive schedules and unproductive attitudes towards stage work. Regarding touring, A Spectacle of Herself is technically more demanding, but we don’t want people pushing themselves as far as they can, or proving they are on board by how much they suffer. We don’t want our team to operate in unhealthy spaces, and we want to have the time we need for our process to happen smoothly, for us to understand the technical context in different spaces, and adapt to what’s possible.

Elena Stanciu: In this transition from solo work to directing a collective of artists - what do you expect the changes to be, in the personal and political assemblages you've had so far?

Laura Murphy: There is a functional reason for this transition, because, believe it or not, I don't always want to be at the centre of everything, all the time! [laughs] l want to carry on being a performer, but I also want more time to work with Nicole, to direct. I'm interested in voices beyond my own and that is the limit of solo performance, especially in my case, limited to one perspective – white, queer, autistic, based in the UK. I'm curious to explore other perspectives, and look at other bodies on stage, explore different skill sets, and look at different ways of moving and being on stage. It will be a different and difficult thing because that removes my own biography from the centre of the work. But it’s important to reflect and learn in a different way.

Elena Stanciu: Are you interested in other disciplines?

Laura Murphy: We talk a lot about different circus disciplines, and there's a whole wealth of writing around different disciplines and their current potential. There’s extensive writing about the relationship between the circus artist's sense of dominance over apparatus (Bauke Lievens writes on this), which is so interesting to explore. But I'd also be curious to work with magicians, dancers, or anyone with a physical practice.

Elena Stanciu: Recent circus critique does indeed call out for circus to be more critical. As an artist whose work is tightly bound to criticality with political stakes, do you see art ever to be apolitical? How do you reflect on this idea of responsibility or accountability for artists to use their platform?

Laura Murphy: I think all art is political; I don't think we can get away from it. It’s a big statement to say art should or should not be something or other; we all need different things at different times. But we could be more political and more outspoken in the circus community. This is really broad brushstrokes, but if we think of training and circus schools, for instance, the focus is really intense on physical training and the discipline, and there’s not the same focus on awareness of what’s going on in the world, as you would have in fine arts universities. But then again, what does it even mean to be more political? What shape does that take? In our company, for instance, we care deeply about how the very personal elements have relevance in a broader context. We already know that it matters, we don't have to have loads of conversations about why politically it’s important to stand on stage naked or talk about masturbation or mental health.

Nicole A'Court-Stuart: In the UK we often talk about shows we’d call ‘issue-based’, when they are more didactic, aiming to make a change. I think sometimes when work is made in a more didactic way it can struggle to acknowledge or remain open to the current political charge of the issue. It suffers from a type of time lag because something is really urgent and you decide to make a show about it, but by the time you’ve done the show, the issue has developed beyond what is acknowledged within the work. I think we get more out of creating situations where elements sort of rub against each other, and there’s some dissonance there, that leads to critical thinking. Then we can bring the contemporary context into that space. I think that’s more valuable, rather than becoming too didactic.

Elena Stanciu: Your work often plays with a duality, of using circus and performance to articulate social critique, but you sometimes express criticism of circus and some patterns of creations and production, criticism which is not uncommon for other voices as well - Bauke Lievens is an example. How does the circus community engage with it? How do venues and audiences respond?

Nicole A'Court-Stuart: From the initial conversations I had about Contra, with programmers and other professionals, there was a sense that it belonged in academic contexts or galleries; that it’s not a piece for theatre or circus or entertainment of any kind; that it’s an academic work. It was interesting to see how criticality was perceived out of the fact that Laura was naked on stage and that there was talking in the piece.

The thing about critical work in circus, a curious thing, is that aerial work is “allowed” to be aerial. It doesn’t have to try to be something else, it doesn’t have to try to communicate an inner state; it’s allowed to be and do what it does: position bodies in the air, although sometimes objectifying those bodies; it is a space of fantasy.

Laura Murphy: Also, traditionally, in traditional but also in contemporary circus, aerialists don’t talk; they’re just bodies, especially in corporate work, where a lot of objectifying of the circus body takes place. With respect to this, I can trace this duality you mention in my work.

Elena Stanciu: Is there a response from the circus community of artists who have to do commercial gigs, and can’t always afford to be political? Does it come as a type of privilege, to be able to create political work and not have to work corporate gigs?

Laura Murphy: Yes in some ways I see it as a privilege, but I also see it as just different. I am not a corporate aerialist, but I’m not saying people shouldn’t do it. I do have a problem with how patriarchy will rule that situation and discipline those spaces. I’m not sure I could even access these spaces - as someone with breasts, hairy legs, hairy underarms, no make-up on. I struggle to operate in spaces where I’m expected to perform a particular version of femininity. Yes, there are problems inherent in that, but there are problems in everything and I would never criticise anybody else for the choices they make. It would be nice if there were some alternative scripts within that situation.

Elena Stanciu: Speaking of alternatives - you're often described as “genre-defying,” which creates this sort of centrality of the art, where a type of marginality is implied, where the rebels of the art form are found. How do you reflect on your own positionality in the art field, and where you are presented or where you show your work?

Laura Murphy: I would say the work is somewhere between contemporary performance and circus. For a long time, we were sort of stuck, knocking on the door of circus, asking to come in, and being denied entry. Because of different reasons - the spoken word, too much critical material, nudity. Then galleries and theatres were not open to us, as long as there was still some circus in the show. It’s only recently that the work gets presented without this resistance.

Nicole A'Court-Stuart: The question of access is also due to a concern with how the work will be received and even understood, particularly in the UK, as venues survive by selling tickets.

Elena Stanciu: How did you navigate this impasse and get past the resistance?

Nicole A'Court-Stuart: Layering humour over heavy-hitting topics will make it easier for programmers to say yes. This happened with Contra. We were able to argue from this position of in-betweenness of the genres, so people who recommended at first that we go to a gallery were more open to presenting it in their theatre because they saw it was funny. Humour has a genuine role in the work, and it wasn’t put there just to make it palatable, but it was interesting to witness this shift in how the work is talked about.

Today we present mostly in theatres, but we’re trying to not be very preoccupied with genre. It is quite lovely to spend time in circus. I feel that the more time we spend in theatre, I can tell that we are not from that world, not originally. I think in circus we are more flexible about boundaries, in how we work and the roles we fulfil, and for our company this flexibility makes more sense.

Elena Stanciu: Yes, genre and discipline boundaries in circus are more fluid, and people are more keen to discuss and explore them. Clowning, for instance, is a discipline that this year received attention both at SMELLS LIKE CIRCUS in Belgium and CircusDanceFestival in Germany, both festivals in which you were programmed. Do you carry out an exploration of your own, in terms of clowning? Is there a change in approach, from Contra to A Spectacle of Herself, in how you work with discomfort as a function of comedy and humour?

Laura Murphy: I often write things because I want to write them and say them; sometimes they end up being funny and sometimes they're not. When I write, it's difficult to imagine how playing might happen, for example - also a strong element in comedic work. I don't think about writing comedy, but I'm a playful person. I like being silly and I like playing with audiences. Lots of the clowning and that playful relationship really happens when I stage the work. When I work with Ursula and I get a direction to deliver in a funny way, I completely block it, because I am so aware it has to be funny.

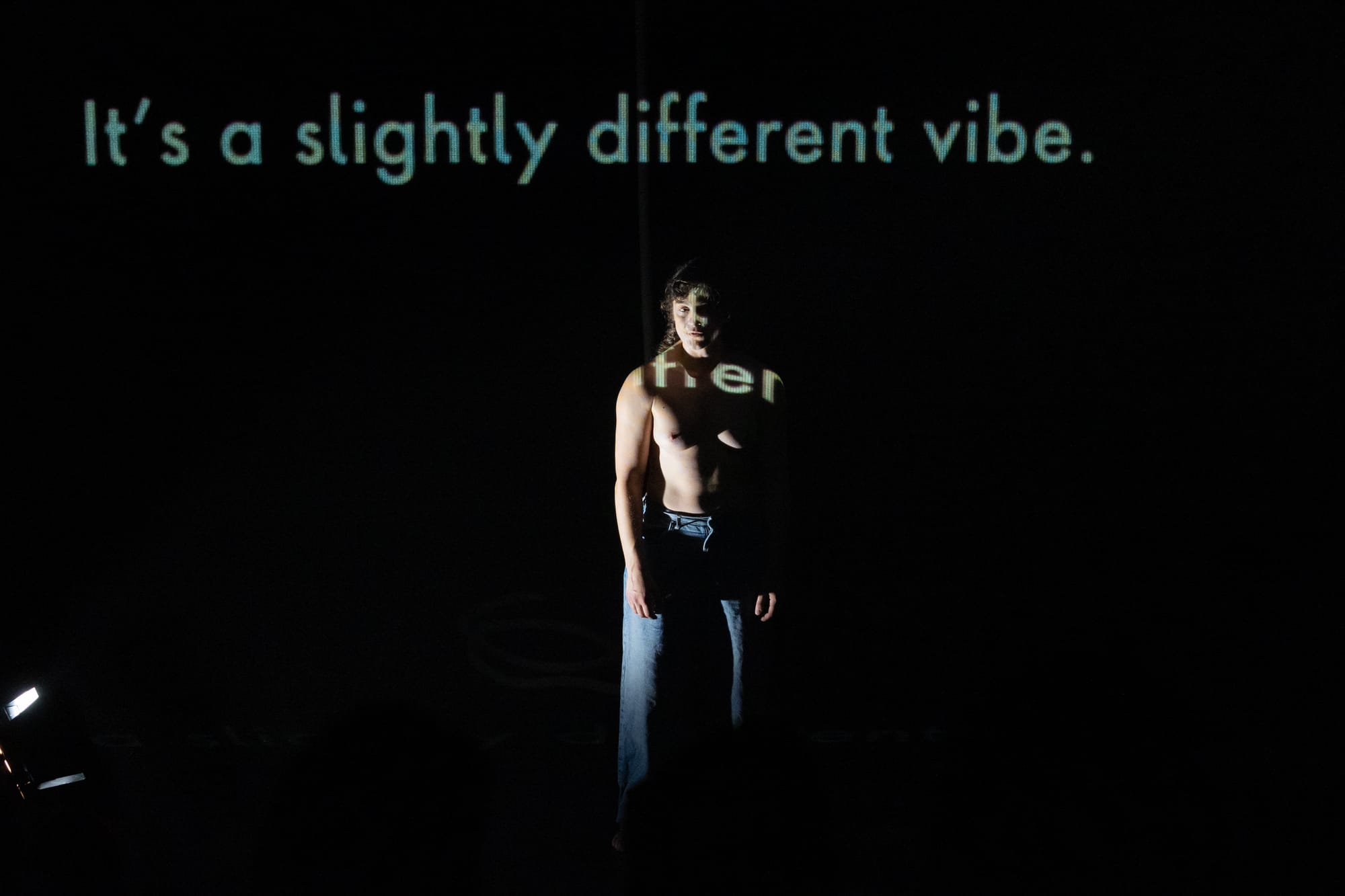

Nicole A'Court-Stuart: I think that's also because humour doesn't come from the content of what you're saying. It often comes from the layering and the ways that things are brought together. Clowning is all rhythm, tone, text delivery, and the dissonances that you create between the content and the way that you deliver it. The element of discomfort is interesting, because: who is uncomfortable? Is it you or is it the audience?

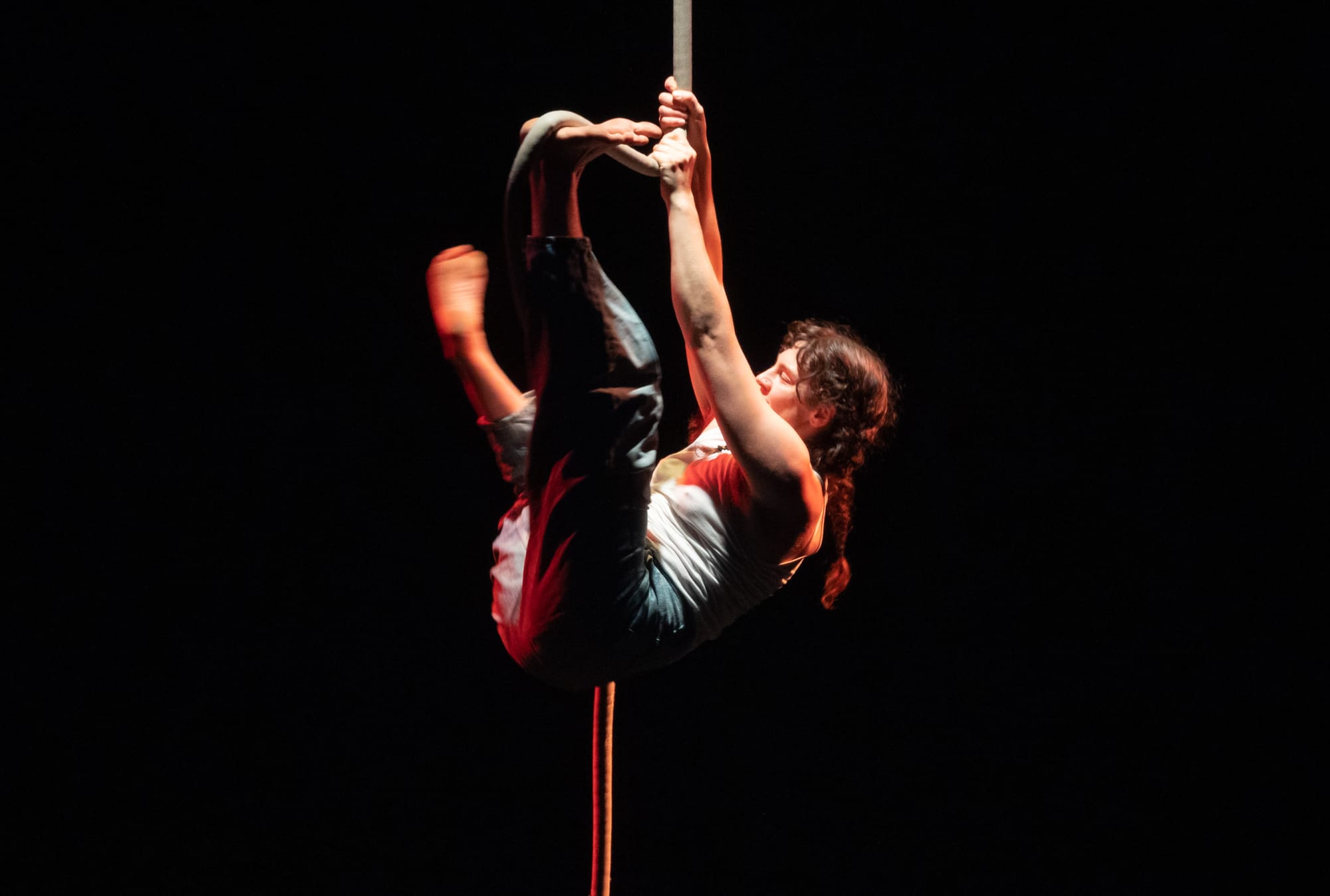

The clown is putting themselves through something which either appears or physically is uncomfortable, but the discomfort is transferred to the audience. We are uncomfortable and complicated and have things that don’t fit well together. We're all a bit of a mess, so there's a kind of empathy that's created in those situations, and comedy is a conduit of this empathy. Sometimes, just being on stage trying to find your way with a box over your head is uncomfortable to watch, but the humour and discomfort can also come from the very context of going to the theatre to see a woman with a box over her head.

Elena Stanciu: Yes, absurdity is very funny.

Nicole A'Court-Stuart: Yes. There’s different waves of comedy that come from discordant, absurd situations and the ridiculousness of it all. In Contra we see a naked woman talking about how many poos she’s done that day. But we also see a naked woman talking with the voice of a chauvinist comedian. The dissonance is funny, but also super uncomfortable. It’s funny because it’s uncomfortable. That’s why I never feel that the comedy comes from comedy writing, but from the delivery, the pacing and the staging.

Laura Murphy: I also find it so interesting how different things are funny in some places, but not in others. Depending on where you are in the world, talking about poo is funny. In some places, it won’t get any laughs. But I still deliver that, because it's politically important for a naked person who might be seen as a woman on stage to talk about poo. It disrupts a patriarchal notion of the female body.

Valentina Barone: I think it’s also a function of honesty when honesty is staged. The performers can stand on stage and allow themselves to do things that are not allowed to other people. Yet at the same time, this act performs a type of unburdening of another person’s discomfort, as it paradoxically creates another type of discomfort. I think it’s so essential to discuss this in terms of the responsibility of revealing, which is personal and collective.

Laura Murphy: Nicole put this quite well; I’ll try to use her words: the stage for us is a space where things that I might say anyway, or do anyway become suddenly socially allowed. We can talk about those things, but it's not like I make a special effort to say it on stage. If I had it my way, that's how every day would be, but there’s more space and allowance for truth on stage.

Elena Stanciu: Do you see your work as throwing the ball to your audience and saying ‘Do something with what I give you?’ Or does it end there because that's a strong enough gesture that you embody those issues or voice them?

Laura Murphy: Yeah…What is the role of performance? I see performance as a tool for reflection, which is really important. Learning about the way that we operate within the world and the way the world works, how our experiences might intersect - it’s all important. It's really as simple as that. It’s obviously sad to hear for example that someone’s husband was in the audience and said “It’s not for me, because I’m a man.” That person clearly missed the point.

In both A Spectacle of Herself and Contra, I critique layers of patriarchy, not necessarily a specific gender, but how patriarchy organises society. It's meant to be a calling in rather than a shaming or calling out. I don't want people to leave feeling bad.

Elena Stanciu: Often audiences are quite generous because they are there by choice and the material resonates with them. Do you encounter people who disagree deeply with the work, who actually push back?

Laura Murphy: There was a man who walked out during the Edinburgh Fringe, where I was performing A Spectacle of Herself, and he was very upset. But he was a bit of a gift to the show because there is a section in the show, where I read a meme that says, “Being a woman or being perceived as a woman or another gender is like being a cyclist on the road and where all of the cars are cisgender men.” We’re supposed to share the road equally, but that’s not how the system works, so you have to cycle at the edge of the road, or there are no cycle lanes, or the roads are not surfaced properly. And as soon as I finish that section this man stands up and walks out, stepping as loud as he could. He was really a gift, he could have been an audience plant, it was perfect.

Elena Stanciu: Do you see your work as activism? Do you ever experience activism fatigue?

Laura Murphy: The opposite actually. The world is exhausting right now and can be really saddening and like everyone I have to take breaks from the news and think about my intake and emotional energy. But I feel making performance works is empowering. Because you get an opportunity to explore and lean into those things in a way that's really personal and really nuanced.

Nicole A'Court-Stuart: It's also a moment of respite, isn't it? It really depends on where you expect the activism to happen. I don't know if we expect the theatre to be the place where the activism happens. I think that it's the space for reflection; people might go away thinking differently, but for the duration of the show, people who feel marginalised or not seen get a sense of freedom and representation.

Laura Murphy: I completely agree! Having my autism diagnosis, and being on a neurodivergent spectrum makes it so important to connect with similar people after my shows.

Valentina Barone: How has the awareness of your autism diagnosis changed your way of operating and shaping your artistic work?

Laura Murphy: I think many people who receive an autism diagnosis experience a sort of freedom to stop repressing the ways they’ve been doing things, which were previously framed as a problem. For years I’ve tried to work out why I can’t work five days a week, nine to five. I can’t work in an office. It's really hard for me to take instructions. I'm very capable of lots of things but there are some environments in which I can’t function.

I've started thinking about the way that my brain works and trying to utilise that a lot more in my writing, which I think has come through in A Spectacle of Herself. I wanted to see what happens if we just throw the rule book out the window, or what happens if today I work within my comfort zone. Or what because I love writing lists and the spectacular self. I’ve allowed myself to be more random and less judgemental in my writing. I’m making more space for beauty, for celebration.

Nicole A'Court-Stuart: I also think our contemporary moment being this real postmodern explosion of everything everywhere all at once, highly mediated presence across the globe - there’s something in this relatable to a neurodivergent perspective. I am also neurodivergent and for me, everything is equally important all the time, and I’ve had to learn how to narrow things down and organise them. I think there’s something in the world today that mimics that experience.

This is why I am also interested in where we go next with our company. Because I don’t think the dissolving of boundaries or imagining the world otherwise will ever leave our shows. I can see a progression from Contra, which was very representational, to A Spectacle of Herself, which is more surreal, and people take very different things from it. I'm interested in the spaces that open up, and what will come next.

This interview will be published in the next DYNAMO Magazine, out in August 2024.