Creative Rigging: a DIY approach to artistic research

As a circus artist working with Rope Design, Saar Rombout developed her specific rope language, entangling her artistry with rigging mastery. Committed to communicating her knowledge using her voice and a collective approach to rigging techniques, her method is creative and playful. It inspires her to find solutions, crossing the line between what is technical and what is artistic. As she explained exquisitely in her Master’s thesis – Rope Design and Rigging Design as artistic practice, the topics of object-oriented ontology, intra-action or object agency are gaining interest, inventing a new propulsive way of dealing with safety. Rigging also has a social component as a practice, and the more consultancy for companies and projects she is involved in, the more she develops the rigging practice of sharing her knowledge with other circus players. On the occasion of her participation at Circus – a safer space for danger with a workshop and as the evaluator for the FEDEC Riggers final event, we exchanged with Saar some words on what her art, artistic research and creative rigging mean for her, and what is evolving in the performing arts sector in relation to this fascinating technique capable of mixing so well the artisanal and the creative aspects of safety.

How did you get captured by rigging?

Saar Rombout: I started both circus and sailing when I was five. I've always worked with ropes and knots, and I became a sailing instructor, also learning a lot about the forces in places with ropes. When I was still studying swinging trapeze at ACAPA, we did not have a permanent rigger yet. At the end of my second year, Noe Roberts, now working as a permanent rigger and safety specialist in the school, came in as a swinging trapeze teacher, and I was always just helping him with the rigging. He visited for about one week a month, but the rest of the time in my fourth year, if something had to change in the rigging, I was usually the person to do it. Thinking about it now it sounds strange since the profession has evolved and become so important for safety. We were still training in a circus tent, and many things have changed since then. I learned a lot in school about rigging in all the productions we were staging. After that, I took several courses, first in entertainment and, later, stunt rigging. Even at the end of my bachelor's, instead of doing an internship as a performer, I chose to do a rigging one in France with Cirque Vost.

At the conference Circus – a safer space for danger, you led a fully booked workshop on Creative Rigging. How did it go, and what is about the rigging module you proposed?

SR: I'm currently the head of a semester-long rigging course at SHK in Stockholm, and I usually dedicate five months of teaching to rigging techniques. It's developed in three modules, and one of the modules is creative rigging. The workshop in Antwerp was a short introduction to that module. Nowadays, many people are experimenting with changing an apparatus, developing a new one or a different rigging setup. And this is interesting, but it can become dangerous fast. So, the idea was to give people tools to experiment with rigging, learn to work with a risk assessment or get creative with rigging by respecting safety. My approach to creative rigging combines brainstorming, making drawings and building scale models. In a scale model, you can already see quite a lot of how things could work. The participants worked in little groups. They had to propose an idea and start building models to figure out some of the things they had in mind. If the solution invented is already not working in a model, then it probably would not work in real life.

Who is the kind of participant you meet during your rigging courses?

SR: This August will be the third year and generally it works better to have a small group. The first time it was all circus artists who wanted to work both as artists and riggers. The second time we ran the course it was a varied group, four women and one man. The participants were very different, we had an architect who wanted to create a circus playground, a visual artist working a little with aerial, and a slackline artist who had already been rigging for a long time but wanted to go deeper into it. They learned a lot from each other. In a creative rigging course, everybody's input is valuable. I teach part of the classes, and I invite some other teachers. I love creating something collective and stimulating the discussions between people because it reminds me that there is not one way of doing it. Multiple ways can work. You must choose the one adjacent to who you are and what is satisfying about your way. Circus rigging is more detailed than rock ’n ’ roll rigging for concerts and events where engines control all the materials and must go up and down quickly. Circus rigging means adapting to every artist, and usually, artists simply need you to realise and adjust to what is required. If you're working as a rigger, you work closer with the artist, especially if you're developing a new apparatus or changing some components. Artists know how they want the apparatus to move or how it does move because they have a specific knowledge of their discipline, which is very valuable. You must work together and build a trusting bond with them.

What characteristics should a rigger have?

SR: I think that the best combination involves a lot of problem-solving and the attitude of finding creative solutions. Curiosity and care are important aspects, too. Many riggers I know, even the older guys who may seem grumpy or quiet, really care about their job, feel responsible and show great care for the artists they work with. They may complain a lot, but they're also going to make sure the rigging is all done well and stay until late. They want to be sure it's all fixed and that the artist feels safe.

How has the sector developed with regards to rigging since you began performing?

SR: Rigging can still be a very macho-male-dominated world, and sometimes the issue is that men in charge want to feel confident and reassured instead of talking openly about their doubts. There are a lot of men who want to show that they know what they're doing, whilst often women feel that they need to know things to a higher level before working. If I came into a theatre for an event as a rigger, I still first had to prove what I knew. And often a male technician will not address any questions to you, since it is not evident to them that you oversee the rigging.

It is also hard to admit if you make a mistake or if you're unsure because it concerns everybody's safety and you want to show that you're confident to make sure that the artist feels safe. Nowadays several rigging courses are only one week long, there are not many longer courses specifically for circus. There are limited opportunities to learn under somebody, so as part of the rigging course I lead the participants must do an internship. It is the best way to get hands-on experience without full responsibility and whilst having a mentor who looks over you, checks things and gives advice. I'm trying to give my students this basic principle: know you don't know and know when to ask for help. Rigging can be broad, and I am not an expert in every aspect. After a five-month course, you know more than before, but it takes a lot of experience to be a professional. What I am also trying to do is bring in different teachers to give them a network of people that they can contact and ask for advice. If they ask me questions that I don't have answers to, I involve the right people to share knowledge and suggest solutions.

How does the technical aspect of rigging influence your artistic research?

SR: Rigging is something that I've always been naturally really interested in, from the technical to the artistic element, but mostly as a combination between the two. It is more teamwork than a solo practice. I had internalised the idea that being an artist or performer was the most important part but in my case, I've always done a lot of things that surround this. I worked as a stage manager, made costumes, and really enjoyed rigging. During my Master’s in Contemporary Circus Arts, I discussed with Bauke Lievens, who was also teaching us some classes. Through this discussion and getting injured I realised that being an artist is not the central part of my artistic practice. All the other aspects feed into each other. An artist is not only what the audience sees on stage. As a rigger or a mover, I am still a part of a creative process, and even if I am not performing, I still feel an artist because it is part of my artistic practice. When you do the lunging for swinging trapeze, for example, the movement of the rigger must anticipate what the suspended artist is doing with the apparatus. You are really doing a duet, with one person not usually visible on stage. In some ways, these attitudes are changing. Nowadays, I feel like most artists treat me equally when I work as a rigger, even though venues still only see the artist and everyone else as support. In a bachelor circus course, you don’t learn what artistic practice is. That does not mean that everybody needs to be an expert in it, but professional artists must understand that their practice is more than just training techniques or creating an act. There is so much more that feeds into artistic practice.

What is your role as a rigger working on artistic projects and how do you use your expertise to support companies?

SR: It differs from project to project but essentially my job consists of creating solutions with them. For the opera project Circus Days and Nights of Circus Cirkör, for example, I was part of the artistic team for the rigging design. I participated in all the meetings with the director and the light, costume and scenography designers. I mentored the riggers to find the best solutions to make everything more efficient. When I work with individual artists I develop a one-to-one relationship with that person on a specific project, usually finding rigging solutions more creatively. For the duet of Tay Lane and Laura Stokes, we worked as a trio, my role was to hide all of the rigging mechanics of the movements. As a rigger, you have the advantage of being backstage with the artists. They feel the value and the relationship more than, for example, a producer or other people on the team. I'm not going to say that I never made the mistake of undervaluing what some people in the team were doing, I'm sure I've also done this, but I feel the horizontality in groups is improving.

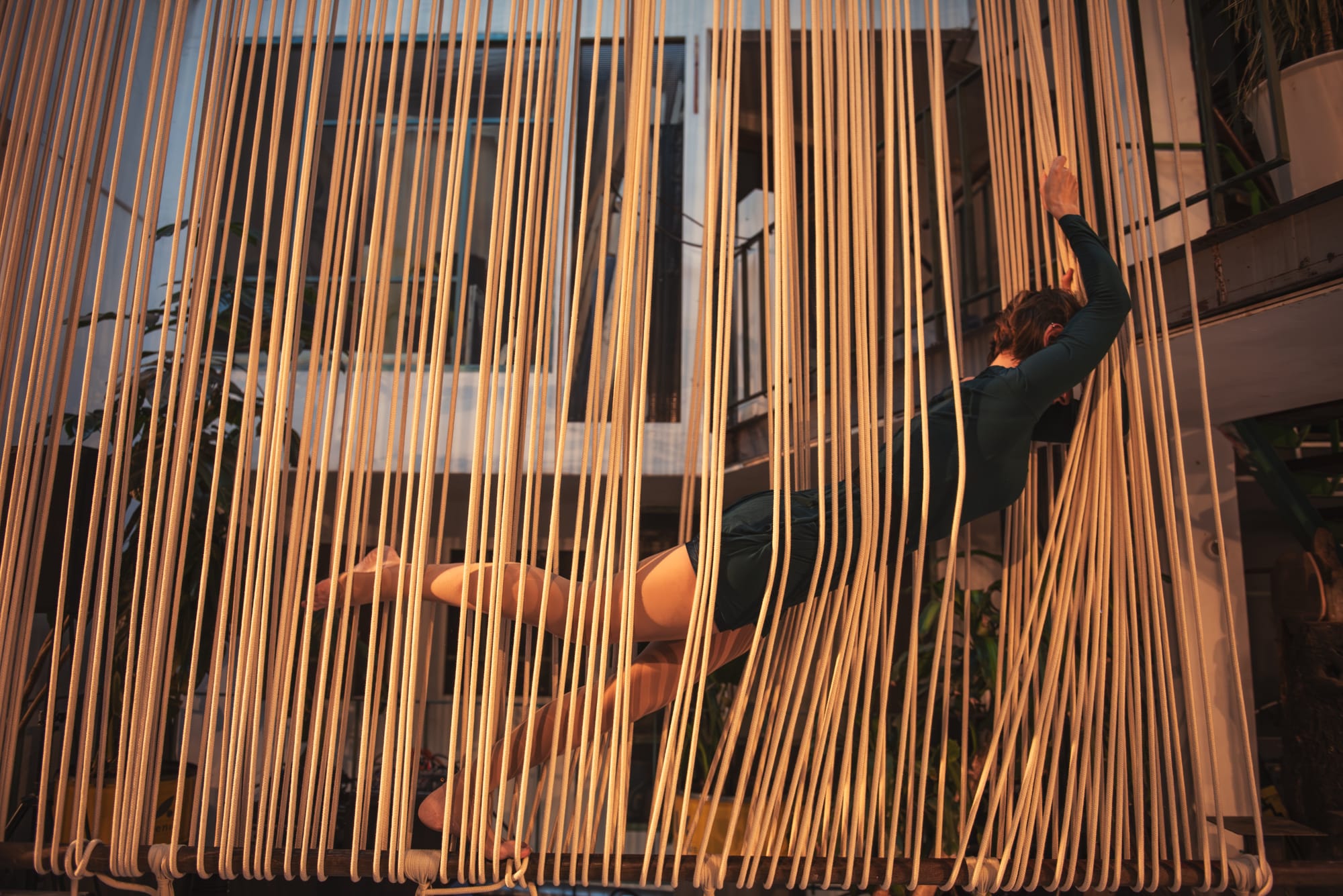

Your relationship with ropes involves an installative and spatial perspective. What is the most important discovery you made through your artistic practice of rigging?

SR: After my master’s degree in contemporary circus arts, I did a one-year course in narrative design. The film, media, scenography and costume design departments worked together to create a course, Narrative Space – Production Design for Film and Media – about all aspects of design for film, media and performing arts and how they are essential for shaping a narrative. We worked with 3D modelling, game design, and making storyboards. In the film sector, production design is an essential part of framing or supporting the narrative. You can really break or make the story through production design. The approach is similar in game design: there is a narrative, but it's not completely fixed because it depends on what the player does too. In performing arts this approach affects the conception of what you are creating in a team. The person on stage is not the only one making the narrative.

The audio-visual essay about my Master’s thesis was part of that course. Each module I went deeper in my artistic research on ropes. The Bubbles theory I detailed in my thesis started from a movement improvisation we were working on. I was working with Fran Hyde, and we imagined a bubble around the two of us moving with that. That experience expanded into the idea of everybody and everything having a bubble around themself. And those different bubbles meet each other. A bubble can also be like an idea or a concept. By coming into contact, each bubble changes. So, all the interactions you have with people around you, spaces, objects, concepts and ideas all come with you. Ideas change and affect your bubble.

In your master’s thesis, you also explore what is object-oriented ontology and the intra-action concept. I found both approaches fascinating since as an artist, you put yourself in a constant position of questioning your circus practice as something else. What are the artistic research projects you are currently working on?

SR: I had a kid a year and a half ago, and he was born with an emergency C-section. In the same week a friend of mine, Sianna Bruce, had an operation. We are both aerialists, so because of this shared experience, we later applied for a residency to look at how you come back after an operation. That week focused on us, but by the end, we realised that injuries or going through relevant changes in your body are essential for circus development. You get a new perspective and look at your artistic practice differently. You start to work in other ways, with rehab exercises, and if you're teaching, you share your experience with others. So now we're developing that knowledge into a project called BodyDiaries, where we want to collect stories of physical artists dealing with obstacles or psychological problems you are not supposed to feel while facing changes in your body. We want to investigate how injuries, pregnancies, transitioning or ageing affect your artistic practice.

BodyDiaries] Saar Rombout and Sianna Bruce Circus Whispers PODCAST

I recently listened to the Circus Futures podcast episode with Alexander Vantournhout, where he talks about the concept of affordance in design. I noticed the ropes communicate the exact opposite: they don’t seem intuitively to push you to use them. They require a high level of manipulation, but if you know how to use them, you can do with them whatever you want. So, I can imagine that in working at an installation, you are in the position of knowing a lot about them and figuring out how the magic will happen: how the audience can discover that they are a tool.

SR: This is interesting because one of my peers’ students in the master's program was also talking a lot about affordance theory and then working with a general audience and letting them play in the ropes. The audience immediately thinks there is nothing they can do with them. But on the other hand, ropes are so present in our lives in so many ways that everybody can do something with them. When I presented my installation Rope Cube in Stockholm, the circus students all started climbing it, all convinced that they could do so, that they could exert a sort of control and be impressive in it. In that case, for example, I found the audience who was there that did not have any circus experience listened to the ropes a lot more, by just seeing what they could do instead of doing something or failing in it.

I want to find different ways and places to create installations for experiencing circus from a different perspective and to find performative ways to continue my research. I am working on an interactive performance installation called Play Space, a circus experience using an interactive rope that originated from my master's graduation piece. Last summer, at the Amsterdam Fringe Festival, the audience could explore the ropes through their senses, guided by my recorded voice.

When I was living in Stockholm, partly during the master's and when working with the circus dialogues continued, I found that that kind of talking and thinking and moving and exchanging about your artistic practice is essential. I'm trying to find connections with other people to continue my research. I got cultural funding from the Netherlands to organise some dialogue sessions as artistic practice exchanges, partly with other circus artists and non-circus people, exploring how I work with circus and playing with the relationship between body, object and space. In a few weeks, I will start a residency in Rotterdam, inviting a group of circus artists for one day. I will guide them through working on what an artistic practice is, sharing different methods and tools that I have developed.

You’ve been recently involved as an evaluator in the RIGGERS project by FEDEC. What did you learn through this experience?

SR: During their first three days of the project seminar in Stockholm at SHK I was involved as the leader of the rigging course and I thought it would be interesting for the students to meet all the riggers taking part in the project, so I asked FEDEC if they could take part at the discussions and participate a little. Soon after, they were looking for an external evaluator and asked me because they knew my work in the field. I was not involved directly in the process, though it was funny because I felt like part of the group, but at the same time also a little bit on the outside, and was the only female among the riggers. When we started to talk about stress management, they started to open up, each of them realising they were not alone in feeling like that. A rigger often works in solitude and feels responsible for another person, so often in schools or companies, they feel isolated. They have all the responsibility without really discussing any of their problems with other employees or with the students because they need to gain a certain trust. In the two-year project, you could really see their trust growing. At some point, they started sharing their experiences with accidents and incidents that had happened, discussing them in a really useful way and thinking about how things could have been done better or learning from each other without judgement. So that aspect has been nice and I am happy the sector is going in the right direction.

The whole evaluation will be available in September. SHK and FEDEC had never evaluated a rigging project before with fixed guidelines about how to do this. We decided to concentrate on seven topics and what has been developed in the events I took part in. I interviewed all the participating riggers through a questionnaire, analysed the tangible and intangible outcomes in the process and summarised all their answers. I wanted it to be readable, especially for riggers, who are not all into theoretical reading. It is an accessible document, aiming to nourish the various players, programmers, producers, and artists dealing with rigging in the circus sector.