I feel a thousand times better when I’m up there than on the ground

Every funambulist embodies a personal style, and in my imagination, Johanne Humblet will always be the first I saw hanging and spinning from a balance pole, making me feel the hit of gravity as if on a rollercoaster while standing still, intuitively imagining that even a straight line could also bend to one's will. I caught up with the indomitable director of the circus company Les filles du renard pâle to chat about her triptych Résiste-Respire-Révolte and discuss what it means for her to be able to surpass one's limits when writing a circus show as a female artist.

In this interview, we dig more into her attitude as a circus director open to working with engineers, constructors and circus artists, experimenting with merging the individual and the collective, discovering the entanglement of aerial technical aspects and the dramaturgy about a collective group of multitasking performers. We see the necessary support beyond fears to create a meaningful performance and make it travel across countries, meeting other artists and blossoming in international collaborations and, sometimes, even in circus visual art projects.

You're Belgian. Your circus training started in Brussels as a child and later, you continued your professional training at Académie Fratellini in France. How is your path as a circus author entangled with the evolution of your shows’ creations?

Johanne Humblet: Yes, I started circus as a child, at l’École de Cirque de Bruxelles and later on, during my training in Paris at l’Académie Fratellini, I trained as a tightrope walker. About 12 years ago, I started as a funambulist [1](high wire walker), because I love heights and I wanted to do something else. I did a lot of work with the balance pole at Fratellini already, because I trained for days and days and hours and hours with the wire. After graduating, I started working as a circus artist, and in 2016 I founded my own company, Les filles du renard pâle. That was while I was co-creating a show called Sodade, and I started feeling how frustrating it could be to create something authorial without feeling completely satisfied; I always wanted to go further.

[1] “Funambulism” is the term for tightrope walking at height, which requires a balance pole to keep balance while crossing the wire. In this interview, the terms “funambulism” or “funambulist” will be used to make a distinction to conventional tightrope walking not higher than about six metres above the floor.

I worked with many companies as a tightrope walker, and I started doing shows as a funambulist. I started enjoying myself and developed things that were new for the practice. Around the time in which we were touring Sodade, I wrote Résiste. I decided to create my own company to put it on stage, and the idea of doing a triptych was there from the beginning. In 2016, I came up with Résiste- Respire-Révolte as the trio of my creation. I knew that I wanted to do that. After writing Résiste, I was looking for people to realise my visions of apparatus among constructors and engineers. I started working with Maxime Bourdon who helped me throughout the creation, especially to find material around the wire. I didn't want someone from tightrope walking for this research; I wanted a fresh perspective to realise the images I had in mind. For the apparatus, and everything that belongs to that, I worked with an atelier of constructors and engineers called Sud Side, based in Marseille.

You found a unique way to re-appropriate the apparatus for your practice by using it in 360 degrees instead of the conventional way, which is typically bi-dimensional. How did you shape this innovation?

JH: You can still invent in this discipline, many things have not been done, yet. Look at the balance pole, for example! It is what helps you to keep your balance. It's your life. But for me, now, it's a partner, a partner I challenge: I twist it in all directions, I put it vertically, horizontally. In Résiste, I bend it in two, I break even the strongest parts. I've modified this object to not just walk on the wire but to be able to surprise. I’m pretty playful in taking risks and always strive to go beyond the limits. As a funambulist, taking risks is crucial, because we're risking our lives. I play with this, but I don’t put myself in danger. For me, life means that you have to take risks! That's what I want to say in every show that I do. You must risk the unknown and go beyond your limits to discover new things.

I imagine that is training?

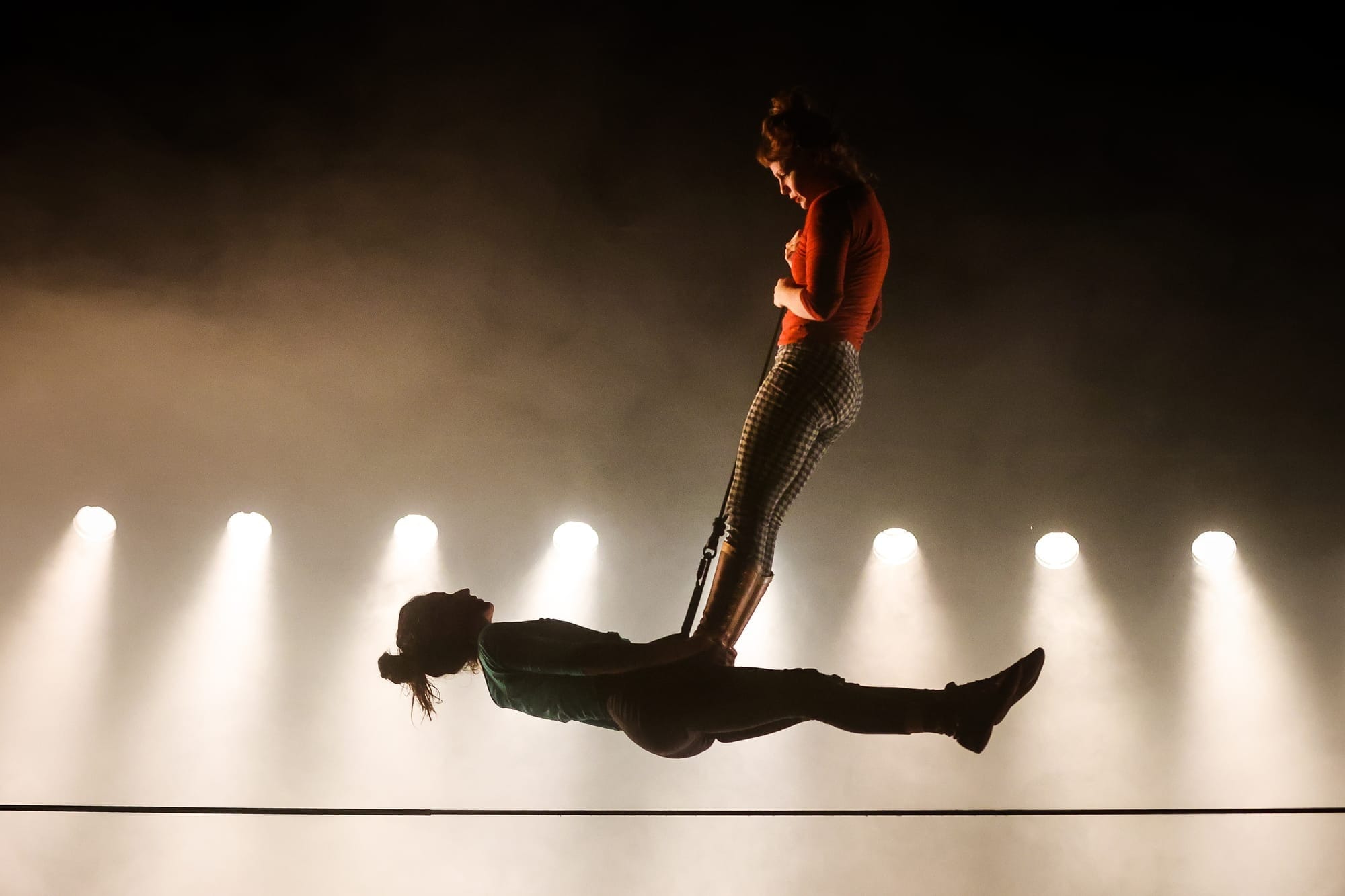

JH: Yes, and it's mainly mental because you need to dare to be uncomfortable. For shows like mine, you must dare to get bruised, to go through crash tests. You have to engage. I put the people I work with in the same situation as myself. I am speaking of a situation of constraint, where they will be obliged to do new things and go into something that may be uncomfortable initially and becomes comfortable only in the end. It's not easy to work like that with artists. It requires a system of support for them. For example, Violaine Garros, the singer performing on Résiste with me on the wire, normally does vertical dance. I wanted to see her versatility on stage, involving her in trying different things, so I felt responsible for accompanying her on the wire. We worked a lot on confidence; developing a sense of safety together is really about offering mental support.

I ask my artists to surpass themselves, which implies I need to be there for them too. Not everyone has the same level of acceptance, and not everyone likes to challenge themselves in that way. For me, it's essential. Challenging yourself makes you discover new things, not only in Circus but also about yourself. It makes you invent. I like to create, I like researching, and I want to explore things you wouldn't expect. This is what being an artist is all about for me: questioning and challenging yourself, your environment and those around you.

What about your body? Has the relationship to your practice changed?

JH: My body is my work tool. I am asking a lot and I'm not very gentle with it. I'm injured all over, my shoulders don’t do well, and I'm in pain. However, it's a decision to carry on anyway. I'm not a great listener to my body and when I have a little something, I am not stopping. To create new tricks, I do a lot of crash tests. It's a guaranteed failure, but it makes me laugh a lot. (Gets out her phone and shows a video of crash tests of Révolte)

In your work, the technique of tightrope walking makes up the dramaturgy. Can you share more about the triptych of shows and the differences between the pieces?

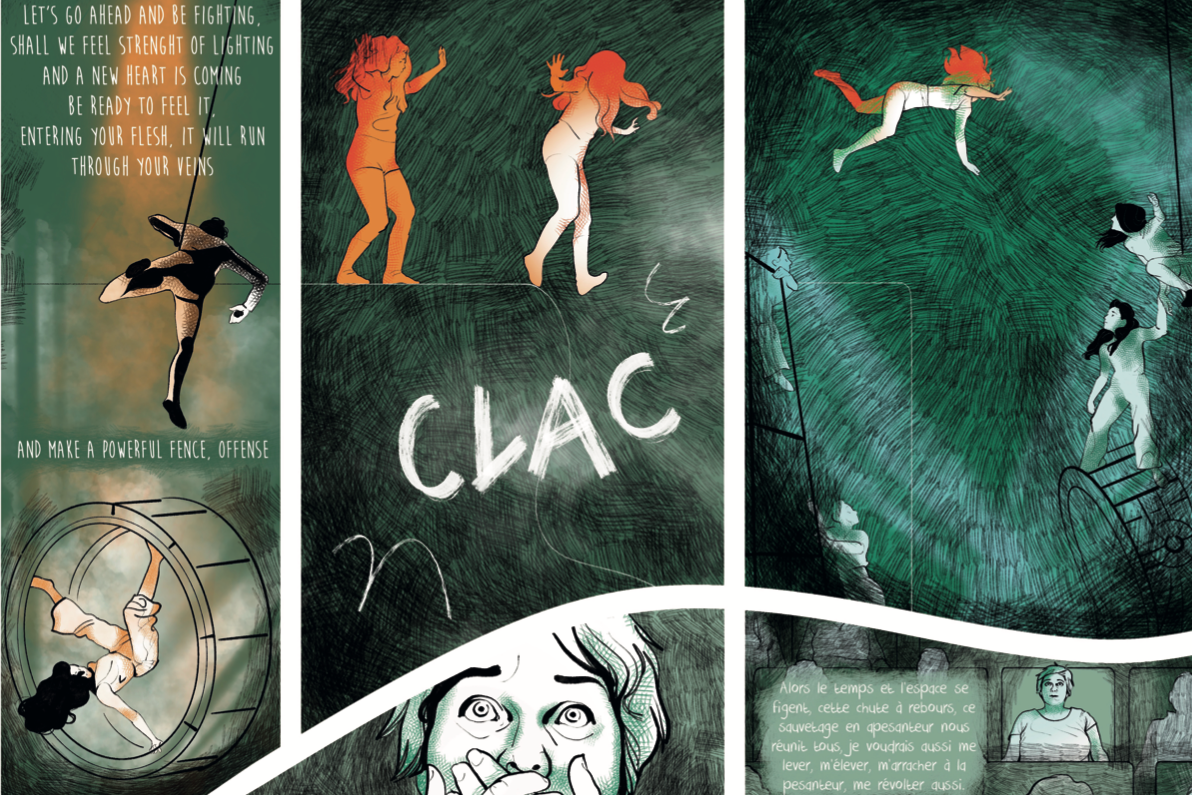

JH: Résiste starts from the individual. There's something very self-centred about saying that you resist whatever happens: the wire that falls and bends... You hold on to it but in a very individual way. There's the singer under the wire, who is also in her own world. We interact with each other but we remain in our bubble resisting alone. In Respire, this expands. For me, it's really about breathing, but above all, it's about the search for freedom and fulfilment. In Respire, I take off layers of clothes, like shedding skin. It's like finally liberating yourself from what's weighing on you, to find yourself again. In Résiste, we resist, but naturally, there's something heavy about it. In Respire, we remove everything that weighs us down, to find our freedom.

I started reflecting on the word ‘Révolte’ in 2016, and I had a meaning for it. Then, I did a week's residency at the end of 2020, and the meaning had changed. Many things were going on, there were the Gilets Jaunes [2] and then there was the lockdown… so “ou tentatives de l’échec” (attempts at failure) was my choice because the first image that comes to my mind when I think of a revolt is coming up against a wall. You go up against the wall because you hope to knock it down. You fail, since it won’t fall the first time. Failure is inevitable. Yet hope is there, so there's the attempt, you think that you'll knock down one single stone, and then maybe another.

[2] The “Gilets Jaunes” was a spontaneous and breaking movement of social protest that started in France in 2018, originally against the increase in the price of motor fuels as a result of the rise in the domestic consumption tax on energy products and that became a national controversy.

For me, a revolt is a need to act, a need for action when confronted with something that doesn't suit us. To revolt, you have to join forces and find people to ally with, and that's what differs from Résiste. Also, once you find someone, it’s not easy either: if that person abandons you, you fall. I point that out in the show, too. The triptych traces an evolution from the individual to the collective. What I'm talking about is the path to revolt, not the revolt itself. The revolt may well begin at the end of the show, but what interested me was talking about the development towards it, and how we can approach each other to arrive at a moment that can change things.

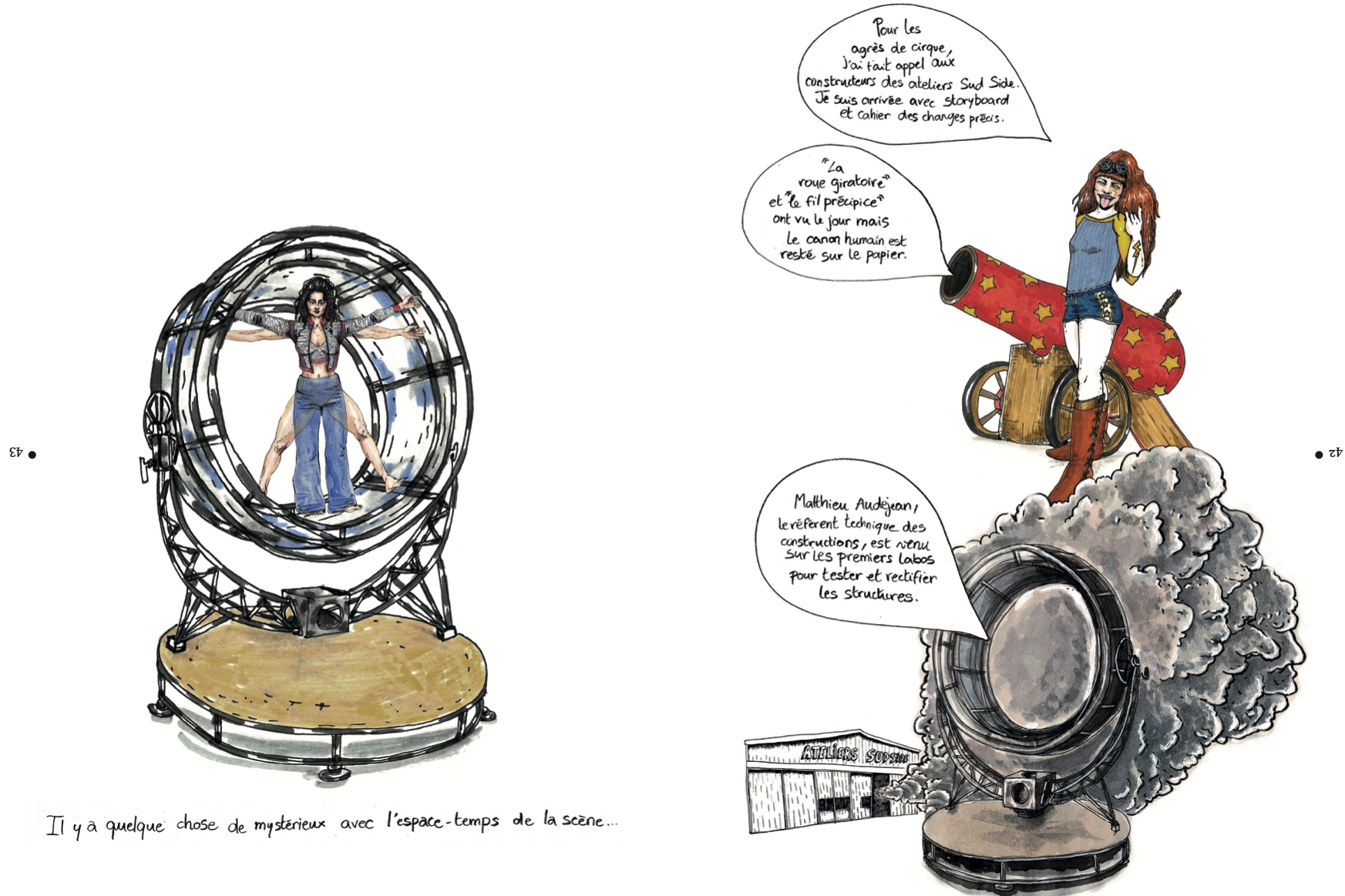

With three female illustrators, Virginie Fremaux, Maya Racca, and Natacha Sicaud, we've created a free comic book to document the creation of Révolte. It's a comic that can be read in 360 degrees. There are different parts: the storyboard, the show as I imagine it in my head, translated by the interpretation of an illustrator, a behind-the-scenes of the creation, and then the finished show. Starting my creation, I had a week of residency during which I wrote the whole show. When I went to see the constructors, I explained exactly what I had in mind for the apparatus. I tell them how I imagine it and then it's up to them to see how they can make it happen.

I'm curious about the wheel you use in the show, that you call Roue Giratoire. Is this a new technique, something you've built?

JH: For Révolte, I originally wanted to have a character who does nothing but run throughout the whole show. In the beginning, I thought of using a treadmill, or something similar. As for the character on it, I wanted it to be a bit like the bartender in the show, doing nothing but running around, to refer to some kind of exhaustion. I had in mind many things to happen on stage, but I wanted one lasting element, a character as a kind of cursor. Little by little, this idea evolved, and the treadmill took the shape of a hamster wheel, representing a person who's caught up in the gear wheel of life and can't get out. A wheel that never stops.

I'm impressed by your decision not to use safety devices. What’s the philosophy behind it?

JH: In Révolte, I'm playing with that. We're attached, we're not attached. At one point, Violaine leaves me in charge of her security, a sign of absolute trust. I refuse to have security when I am on the wire because it technically hinders me from doing what I am used to doing. It doesn't work; it actually bothers me, and in the end, it's even more dangerous. What's more, if you are attached, you're telling your brain that you could fall, so you're not awake in the same way. That's the way I work, and I am aware that not everyone works like that. But for me, it’s a technique: even before I can imagine the fall, I can feel what's happening. There, all my senses are hyper-awake - I see better, I hear better. That's the state I'm looking for when I'm on the wire, it’s total control. It is my element, yes. I feel a thousand times better when I'm up there than when I'm on the ground. On the wire, you have no choice but to live in the present moment. You can't lie or cheat. You're forced to be there, as you are, and finding that in life isn't easy. I'm fine up there.

Can we talk about feminine writing, when we talk about your company?

JH: Yes, absolutely, it's very feminine. I'm a woman, and as such, I have to deal with lots of things. Like all women, at first, I wasn't immediately considered legitimate when I wrote a show. We have to prove more than others. I think that there is a reason why the shows are called Résiste-Respire-Révolte. Those are strong topics always hinting at an idea to give and show more. However, in all my works, I don't feel obliged to prove myself or show off, but I was confronted by people who didn't believe in my projects, and thought it was too big for me. I was told to start smaller, but I knew what I wanted. As time went by I proved that I realised what I was saying. So, yes, it's a very feminine style of writing, it's sensitive to the notion of fight because I feel that I have to defend what I do more than others. These things raise questions in me, but they don't stop me. I wouldn’t say that my pieces make feminist claims, but they are extremely feminine.

Your company is an extended collective. I imagine that the feeling of belonging to a team is very strong, especially when working at such heights. Do you feel supported?

JH: My colleagues are more than just support. They're a real team and I rely on them a lot. I count on them for other projects as well! Jean Baptiste Fretray, for example, is the one who did all the music composition for Révolte and parts of Respire, and he also works for the projects we are developing in Cameroon.

VB: Yes, I saw that often you do work outside of Europe. What is this Cameroon project about?

JH: The tight wire doesn't exist in Cameroon. I've put together a team to go there, and we gave children classes to make them discover the practice. Recently we published another comic book with a Cameroonian illustrator to document the journey - La go qui waka sur le fil - and there's also a Franco-Cameroonian music project with a Cameroonian singer. The idea is to share, meet, and develop something long-term! Over the next three years, we are also developing a project with the Institut Français du Cameroun to create a centre for Street and Circus Arts in the country. This project is artistic, educational, and cultural, but it's also social because we've already started setting up workshops with street children.

VB: Do you want to share with us what you are cultivating for the future?

JH: In 2025, we're creating a small 20-minute format, Roue Giratoire, which will debut in March, only with the wheel suitable to perform outdoors in the summer. After that, I've got another project with big heights, Hors Ligne. This will be a complicated one to create, and I need to take the time to do it now. It could be for 2027. I have something else in mind for indoors, a bit in the same vein as Révolte, where I’d love to go for something more dreamlike, diving into the philosophies of the wire, vertigo and emptiness. I like to mix the arts, and I want to mix the real and the unreal! Nowadays, I'm contacting quite a few circus schools to look for young people, since I am searching for doubles. We've got a lot of shows programmed, and I can't be on stage all the time if I want to create as well.

In 2025 we're also developing another international project in Brazil, for the 2025 France-Brazil year: many other surprises to come! I want to pass on the material as well. It's not easy to find people who have the technical level and who really want to get involved. Tightrope walkers who don't just feel the practice, but who ask themselves what there is to convey. There are some complicated things to get across, and I want my artists to get into states of mind that are completely crazy!

So it's difficult to find people who have a passion for this and who are willing to risk the unknown. Sometimes I'm afraid because I tell myself that when I stop, my material will stop with me. Yet everything I do is new, and I'd like it not to die with me. We've got 60 shows next year, and I'm offering work! To continue this reflection, during the Circa 2024 festival, I organised a discussion table with various partners on the theme of acrobatic commitment in the circus. I'm committed to continuing to organise discussions on the theme of risk-taking in circus.

VB: Nowadays, there are a lot of concerns about training in contemporary circus. In the past, the body has been used a lot without thinking of preserving or maintaining it. Today, there's a different awareness.

JH: Yes, but for me, you have to push through. As I said, my shoulder is injured, but I've chosen to continue. I'm aware of it, yes it hurts, but I'd rather buckle down than stop, only to eventually feel less pain, but not to be happy in the end. A choice like that is absolutely conscious. I need to push myself to enjoy myself, to develop my technique, and to have fun! I am aware that this is not the best solution. Nowadays we have a lot of knowledge and means to take care of ourselves while, at the same time, being able to overcome certain pains to go even further and push back our limits! You must be able to combine the two, but circus and working with the body, for me, means going beyond yourself.

*translation and editing in collaboration with Meret Meier