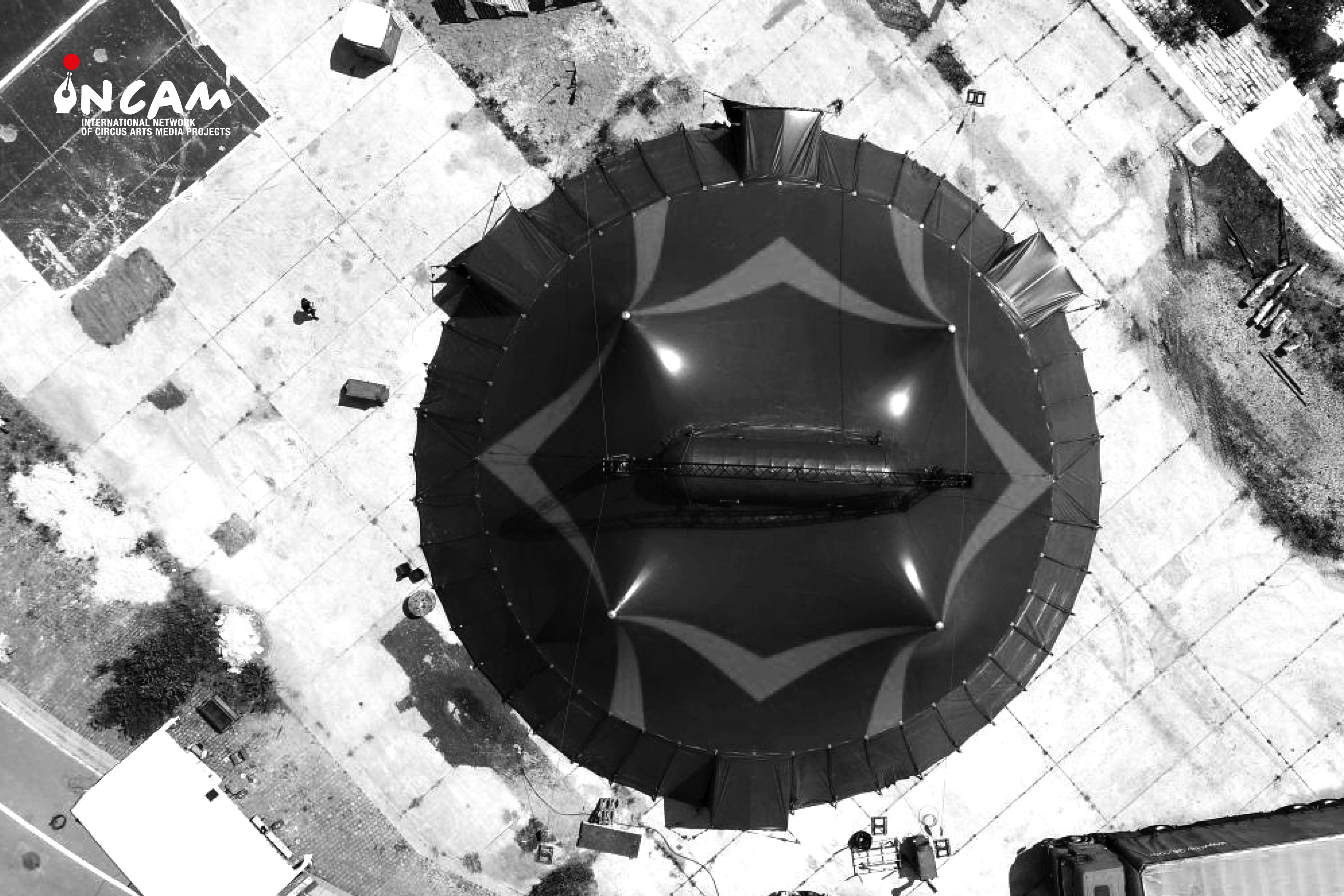

Re-thinking urban space: the big top in the city landscape

This article is part of IMAC#2, the inter-magazine circus festival project which brings together 3 international circus magazines, Around About Circus, Juggling Magazine and StageLync, all part of the INCAM network, and students from the Université Libre de Bruxelles, who share their thoughts on circus architecture. The analysis of historical and contemporary circus buildings is thereby used as a starting point for discussions on broader issues concerning artistic, social, cultural, and historical interrelations. The exchanges that took place during the international conference New Circus. New Architectures at Latitude 50 in November 2024, offered a source of inspiration. Their diverse backgrounds—ranging from literature, journalism and acting, to cultural studies—bring unique perspectives, whether they were familiar with the art form or newcomers. They are united by a curiosity for performing arts, which led them to the MA Arts du spectacle program, offering exposure to various art forms, including circus. As part of the Circus|Studies, an interdisciplinary and international research project led by Dr. Franziska Trapp, theatre students explore circus dramaturgy, collaborate with emerging artists, and engage in performance analysis and critique. Their experiences culminate in an MA thesis or articles like the following.

It's Thursday morning and you have an appointment in the city centre. Just as you're about to pass through the square to reach the bus stop in time, your route takes an unexpected turn, with a heavy goods vehicle blocking your path. More than just a lorry, there are a dozen or so, people in your path, moving trusses and manoeuvring drills. That day, you may take a diversion, hoping to arrive on time. The next day, however, you might be curious enough to ask these strangers about the reason for the change to your daily route.

This is a question often answered by Vincent Bruyninckx, co-founder of the circus Collectif Malunés, which performs outdoors and under a big top, and who kindly agreed to give me an interview. It was while listening to his talk at the international academic conference New Circus. New Architecture? that I asked myself the following question: at a time when contemporary circus is becoming established in cultural institutions, within theatre programmes and even in the construction of new buildings, why choose a big top?

I'd like to think about answering that question by following the same route as that interrupted Thursday morning. Outside the theatre, it's the big top that comes to its audience, rather than the other way round. Vincent describes the set up of the big top as a form of invasion into the daily lives of residents, with all the advantages and disadvantages that implies. From then on, the main challenge for Collectif Malunés is to succeed in creating an atmosphere of togetherness for on average, one week with three performances.

Often, in addition to being open to passerby conversations and questions, this approach takes the form of organising drinks inside the big top. Depending on the cultural initiatives in the town where the collective is operating, they make their space available as a place for reflection, work and creation, but above all for discovering a specific system and its possibilities.

Being open to all is the key to the collective's artistic practice, and the big top is a highly effective medium for maintaining it. As well as disrupting the urban landscape, its aesthetic appeal tacitly appeals to a wide variety of audiences. Our collective imagination of the circus, contemporary or otherwise, has largely crystallised around an image of the circus arts from the 19th century, as Franziska Trapp describes in her book Readings of contemporary circus, ‘clowns, trapeze artists and, above all, the big top as a place accessible to all.’

Just as the theatre is constantly fighting to open up against its bourgeois reputation, established and re-established over the centuries, the big top has its own historical connotations, which already say ‘welcome’. Collectif Malunés is well aware of that and plays with these dramaturgical codes. Their artistic approach has led them to see their ring as an arena, built as low as possible below the tiered seating. Beyond its circularity, this device offers another way of rethinking the place of spectators in relation to the theatre, for example.

As far as audience perception is concerned, Vincent Bruyninckx notes that the type of show offered and the theatre in which it is programmed, play an important role. This is particularly true in the case of BITBYBIT, the show he performs with his brother Simon Bruyninckx, in which they are held in a relationship of interdependence by mouthpieces connected with a steel cable. BITBYBIT is highly performative, co-created with the performance artist Kasper Vandenberghe's MOVEDBYMATTER company, and the images that emerge can be frightening, despite the lightness and humour of the piece.

The world of performance art, an artistic field that is still very compartmentalised, is thus confronted with the more open world of circus. Of course, circus performers are well versed in the work of the marginal, on the edge of risk, fear, discomfort and acceptability, allowing them to think about the accessibility of the work. However, even though Belgian and French cultural policies are keen to open up the arts and make them part of the process of creating social bonds and bridging identity and class gaps, there are still far from enough places to host big tops.

The experience of Collectif Malunés bears witness to a clear lack of suitable tented spaces in our urban landscapes. And yet, cultural democratisation is a process that lies at the heart of Malunés' practice, as well as that of other circus artists. If cultural policy really aims to give culture the means to build community, where are the infrastructures to welcome them? We would never have come across a big top, the artists and the experiences that inhabit it, if the hypothetical town in our story of an unusual Thursday morning had not had the land to host it.

For Vincent and the collective, this issue can be approached from several angles. The first is to raise awareness of the possibilities offered by tents among those involved in urban construction, from architects to governments. The second is the need to support the emergence of circus companies so that the offer is consistent and encourages the creation of suitable sites. Thirdly, a desire to help the general public discover the potential of the big top. Consequently, in the field, Collectif Malunés is seeking to work on all three fronts. Firstly, its mere presence in the cultural field, and its choice of the big top, initiates discussions with the local authorities as the tour progresses. Secondly, the collective attaches great importance to passing on the knowledge it has accumulated through its sometimes somewhat chaotic experience in the field, which they want to make more accessible to future generations. Finally, as mentioned earlier, they are working to put in place systems that encourage discussion and welcome a wide range of audiences.

Why the big top? The answer is far too vast to unfold in a text shorter than a novelistic saga. I have chosen to talk about cultural democratisation through the effects of the big top on access to art. I could also have talked about the dramaturgy of the circular device or directed my gaze towards the communities of the big top profession, whose operation is necessarily based on mutual aid. However, the issue of accessibility raises other questions about the space given, or not, to the community. Why is there never, if ever, a big top in my town? Where can I come across a circus, when I'm walking around my neighbourhood? Where, in concrete terms, are the spaces for building social links to our governments' cultural policies?