Why Circus? A report on the RagBag Festival in Kerala

My invitation to the RagBag Festival in Kerala arose from the, in India, highly unusual approach of making contemporary circus a central theme of a performance festival. Sasikumar Vallikkatte, theatre festival director and artistic director of RagBag, and Abhilash Pillai, director and head of the School of Drama & Fine Arts at Calicut University in Kerala, have been working for several years to integrate circus as an art form into the contemporary Indian theatre landscape. Pillai, who fought for artistic and structural innovation at his academy during his time at the National School of Drama in Delhi, is fascinated by circus and its ability to explore vertical space. The circus was a part of his PhD and became the medium of his large-scale theatre pieces, including a circus series and Talatum, based on William Shakespeare's The Tempest. The latter was performed in a circus tent together with circus performers, theatre actors and puppeteers.

Circus in India

Although circus has an extensive history in Kerala, today it is in the process of dying out completely. At the beginning of the 21st century, there were still 23 active circuses organised in a national association, but today, in 2025, there are only two left. Horrific incidents of abuse and miserable animal husbandry have led to an increasingly poor reputation and greater marginalisation. In 2013, the Indian government banned the use of wild animals in circuses and child labour in performances. Economically, these were two cornerstones of Indian circuses that allowed them to keep the costs of their productions low. Alternative circus models to this system, which in many ways had not changed since the 19th century, were (and are still rarely) known. In India, the circus suffers - and unfortunately rightly so - from a bad reputation and a constantly declining number of visitors, as well as a lack of young talents. Working in the circus is not perceived as a career option, but as a life-sustaining emergency solution.

Even though, the Kerala circus tradition is extraordinary, dating back to the late 19th century, when Keeleri Kunhikannan, a Kalari martial arts teacher from Thalassery, began training acrobats for the big Indian circuses. In 1901, Kunhikannan opened his own circus school, the All India Circus Training Hall in Chirakkara, a village near the town of Kollam. This school went on to produce several famous artists as well as several Indian circuses (including the Grand Malabar Circus, the Great Bombay Circus and the Gemini Circus, which still exists today) and Kerala became known as the cradle of the Indian circus. With the death of Kunhikannan in 1939, the circus academy slowly died, and the circus - like everywhere else in the world - became less and less frequented with the advent of cinema and television. In 2008, the Indian government announced plans to open a new circus school in Thalassery, but the project was never realised. In fact, the Indian circus is struggling rather unsuccessfully to adapt to a contemporary circus concept that differs from the model developed in the 19th century with its codes, stereotypes and power structures. There are no new or contemporary circus currents. Very tentatively, a free scene of jugglers and fire artists is developing, fuelled by an annual juggling convention in Goa. But here, circus is a leisure activity and by no means a promising artistic career option.

The RagBag Festival aims to shed a new light on circus. Against the backdrop of a circus history and reputation that is heavily tainted with negativity, it is highly appropriate to connect with a completely new form of circus, which itself marks a radical break with traditional circus in its European history: Contemporary circus as an innovative art that brings new forms of expression to Indian stages and thus corresponds to a new modern consciousness of the population. Contemporary circus is interdisciplinary, spectacular, low-threshold and political, at the same time. In this respect, the festival programme was highly innovative. Programming circus together with traditional and ritual theatre forms is a political act, a form of protest against the rules, which until now in India have strictly separated art forms from each other.

The RagBag Festival as a place of body-based experiences

The festival concept revolves around the body and sensory impressions. This connects with an ancient Indian tradition: in many of the diverse Indian theatre forms, body language clearly takes precedence over the spoken word. The Western separation between body and mind is unknown; physical expression is deemed to be on equal terms with the spoken word in terms of communicative potential. Here too, the coherent reference to circus as the most physically intensive art form is evident. In the festival, it is combined with a food market that brings together cuisines from Nagaland, Bengal, Nizamuddin (New Delhi) and Sri Lanka, and the permanent crafts exhibition of the Arts and Crafts Village, which is home to the festival. Physical accessibility is at the centre of all three festival components (enjoyment, crafts and performing arts). The three areas are highly accessible and low threshold because they can be physically experienced, understood and communicated by anyone. Consequently, the festival director Sasikumar does not refer to his work as curation, but rather as ‘sensing’, i.e. feeling, grasping or scanning the programme.

According to him, the hands play a decisive role in this - very much in the sense of traditional Indian dance with its rich hand gestures, the mudras, as well as the craft of art, in which the haptics of material, surface and form are felt. It also refers to the loom, which is given a lot of space in the Arts and Crafts Village. The loom serves as a metaphor for the use of hands in creation, for the weaving of stories and meanings and for the processual. It also appears again later in the festival during the concert Dear Swan by singer-songwriter Jaleel, who sets poems by Indian poet and weaver Kabir to music. In the literary introduction, weaving is placed in the context of intertextuality theories by Kristeva and Barthes to emphasise the processuality and the becoming of a text or work of art and its different, changing aggregate states, in which the body is yet again, included.

The interplay of tradition and innovation

The interweaving of theatre traditions and pioneering approaches permeates the entire festival programme and is also evident in the choice of the opening performance. Mudiyettu is a traditional Hindu ritual theatre from central Kerala, the content of which is widely known in India: the goddess Bhadrakali fights the demon Darika and defeats him. Only male performers of the goddess and demon figures with rich costumes, headdresses and masks, as well as a drum orchestra, are involved. There is also a character called Kuli, who, as Bhardakali's alter ego, caricatures a woman from the lower classes and makes jokes between scenes, lightens the sacred atmosphere and jokes with the audience in the style of typical street circus clowns. It is interesting to see how the actors deliberately leave their roles between scenes, only to become obsessed with their characters again.

Apparently, slipping in and out of character during the play has its own tradition in Kerala's Kutiyattam theatre. According to the festival director, Mudiyettu had the function of an introduction, in which themes of the festival are already hinted at: the costumes and masks as traditional handicrafts, the humorous, the theatrical as-if and the performative, the music and the percussion. Percussion reappeared on the second day of the festival in the form of the world-famous concert The Manganiyar Seduction. Here, Muslim and Hindu musical traditions merge in an ecstatic presentation. 38 musicians, all men in turbans and robes, sit or kneel in red-wrapped booths that are stacked in four tiers and illuminated.

The music performance was conceived by Indian director Roysten Abel and is a real crowd-puller - on this evening, around 200 people were the largest number of guests on the site. Another contribution to the historical Kerala theatre tradition was the shadow puppet show Tholpavakoothu, an ancient temple art form of the Kali temples in northern Kerala, in which artistically designed two-dimensional leather figures are used. The figures are moved with the help of sticks, and their shadows appear on a screen that is lit from behind by a row of oil lamps. The performance consists of a poetic story from the Indian epic Ramayana recited in Tamil, Sanskrit and Malayalam and the moving figures on the screen. Within the festival organisation, the Tholpavakoothu performances are combined with innovative, new performance influences of today.

The international performance contributions were characterised by audience contact and socio-critical content. Many artists used the direct address to the audience, such as the Canadian Banan O Rama, who included a father and his child in his street performance by having them hold the slack rope he was walking on. At the end, he explained that he was concerned with trusting a stranger and resisting the dictates of fear of the other. It is up to us to decide what we want to believe. Wooooow! is a feminist clown performance that aims to empower women and settle accounts with the patriarchy. Only men were brought on stage by the Spanish clown La Churry and subjected to various situations that helped La Churry to feel her own power or to assert herself in the patriarchal system. The tasks involved a lot of physical contact and were challenging for the Indian men involved, but La Churry's clown charm always provided the right setting. The audience, and especially the female audience members, celebrated her. In the fanciful interpretation of Alice in Wonderland, shapes and objects become magical play partners for Danish dancer Tilde Knudsen. The piece is a tribute to the power of the imagination and the careful handling of objects.

The Belgian's Shadow Dance, designed by Jesse and Ben De Keyser/Sacred Places, was technologically innovative. A magical water curtain forms the stage for a projected acrobatic performance. The audience experiences a misty dance of ghostly beings that resembles a supernatural apparition. Catwalk by the Dutch group Zwermers is based on a very simple dramaturgy: two people (one female and one male) constantly change their clothes in a monotonous procession. What is revealed in this minimalist performance is the infinite diversity of human identity. Themes such as consumerism, fast fashion, gender fluidity and individuality become subtly visible and ultimately refer to simple human condition. However, the outfits chosen described a Central European identity, and it remains unclear whether the subtle meanings behind them were also legible for the Indian audience. My Wing, by the French company Yifan, is a poetic tale of sudden loss and the ability to draw courage and joy from it. It was told in a poignant and humorous way using object manipulation, balancing skills, live music, and text interludes in Malayalam. The audience was touched and enthusiastic.

The most spectacular contribution was undoubtedly Cubo from Italy. A truss cube in which four aerial artists performed, was suspended from a monumental crane. Accompanied by loud beats, pop music and light projections, it was pulled up to a height of 50 metres. After the 40-minute show, some spectators told me that they were completely electrified and felt as if they were floating, as they had never seen anything like this before. The show, for which an immense technical effort had been made, was intended to be a statement in favour of the innovative, the spectacular and the unmissable new combination of modern circus art and technology is capable of.

The festival production Oru Poomala Kadha

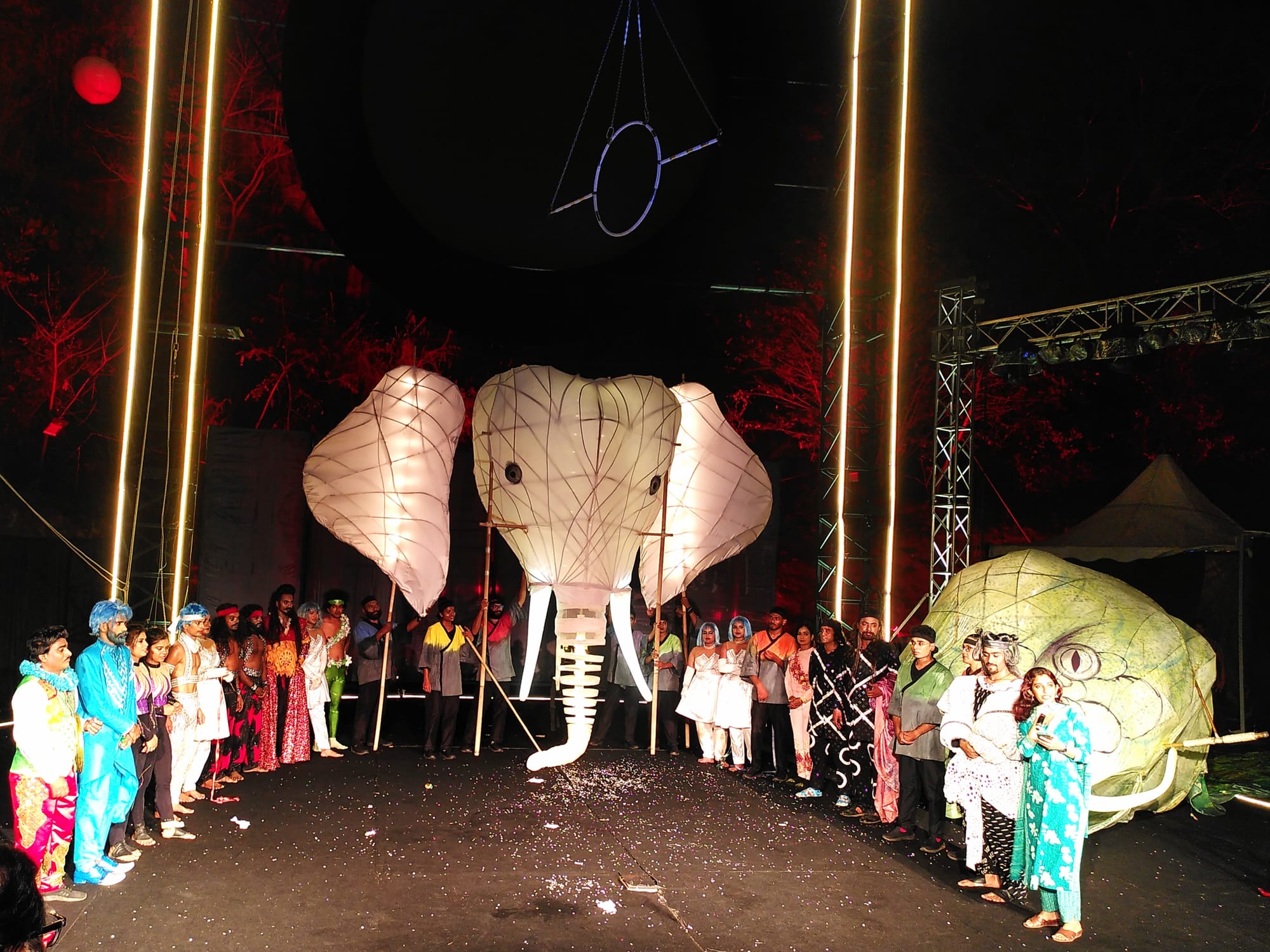

The most significant play of the entire festival, however, was Oru Poomala Kadha, the interdisciplinary in-house production of the Kerala Arts and Crafts Village in collaboration with Arnav Arts. An international creative team consisting of Abilashi Pillai (director), Dr Peter Cooke (costumes and scenography) and Giuseppe Lomeo (music) came together here with almost 20 performers from the fields of acting, contemporary dance, circus, puppetry and video art. The commitment of the technical team led by Firoz, Sourav, Maithreyi Kuhu and Sasibhaskar is also worth mentioning. In a 15-metre-high circular stage structure, a hybrid performance that aimed to redefine performing arts was created within one month. The piece is based on the myth of Samudra Manthan, in which the devas (gods) and the asuras (demons) search for the elixir of immortality. To obtain it, they stir the cosmic ocean of milk, using Mount Mandara as a stirring rod and Vasuki, the serpent king, as a rope. Pillai's staging was strictly oriented towards the original myth and its usual figures. Other levels of interpretation were achieved through the video projection and the elaborate costumes, and of course, through the revolutionary use of circus artistry. The video clips showed, for example, haunting images of war and violence, as a critical allusion to the government's approach to the Ukraine war, or images of mountains of plastic waste, which demonstrated Pillai's concern to negotiate ecological issues within art. The director is known in India for his subversive theatre, which aims to provoke and stimulate thought.

Regarding circus artistry, it was used within the theatrical logic of action to represent certain figures or situations in a particularly impressive way with the help of the appropriate circus discipline - such as the gods in the upper celestial sphere as graceful aerial artists. The approach corresponds to European theatre-circus, in which circus disciplines are used as decoration and representation - and less to a contemporary circus approach, which uses the inherent meanings of a circus discipline. Even if the technical level of the artists was rather mediocre, it is consistent and far-sighted to work with an Indian cast, to sow the seeds of a new movement here, and not to fall back on the many very well-trained Russian artists who have been flooding Indian circus for several years. Moreover, the very fact that the circus occupies such a prominent position in the piece stands for the pioneering approach and strategic foresight in building a new Indian circus movement.

IdeaBag - synthesis of visions

The diversity of perspectives, visions and discourses was to be reflected in the IdeaBag, the festival's discussion format. There were three different panel discussions: one on the topic of tradition and innovation in circus and performance art, one on pluralism of knowledge systems and one on tourism and cultural heritage in Kerala. My exchange with the budding cultural scientist Bala Mohan started with the different circus histories of Germany and India and the current status quo of circus in both countries. Referring to the visible circus elements in the RagBag Festival, we talked about the immediate, affective power of circus experiences and how the circus of today interprets and makes accessible themes such as trust and togetherness, role models and body images and the relationship to objects and our environment. We also discussed the aspect of artistic innovation and realised that the central concept of Indian artistic pedagogy is to promote imitation, and hardly ever experimentation or personal artistic research. We concluded that an approach of unbiased research, deconstruction of the existing practices and free experimentation is destined to be the central starting point in shaping a new form of circus in India.

The first RagBag – a remarkable start

The RagBag Festival has made an impressive start in breaking new ground, realising ideas and rethinking live art. In the spirit of the ‘ragbag’, it has evolved to symbolise the bag full of things that are reassembled and reused by virtue of imagination. Or, as Sasikumar described it: ‘a celebration of human capabilities.’ It became a meeting place for people from all over the world. And it utilised the power of circus to be both: low-threshold and progressive, touching its audience with both grand spectacle and quiet address. I can only hope that RagBag will become an annual event and that the vision of perpetuating circus as a distinct and valuable form of theatre tradition in India will be realised.