Smells Like Clown Spirit

Reviews' report from SMELLS LIKE CIRCUS 2024

[coordination & editing Valentina Barone, proofreading Ruby Burgess]

Every two years, SMELLS LIKE CIRCUS questions conventions, combining circus, performance, music, dance, theatre and talks. The nuances explored during the 2024 edition zoom in on the figure of the clown. All of this spans from the slimy, colourful interventions of Micha Goldberg, to the dancing complicit companionship of DOS, to the ambient morphing and mime of Rachid Laachir, the cynical juggling cleverness of Sacékripa, and the theatrical posthumanism of Geert Belpaeme, among others. Authors from Flanders and the international community gather together, stretching the formats of circus and renewing aspects that challenge the genre norms. I attended the festival as a guest, to be part of the INCAm meetings thanks to Circuscentrum, as editor-in-chief of Dynamo Magazine and as a collaborator of Around About Circus. In the following, I revisit some of the performances with a look at appearances made by clowns and clowning.

In its seventh edition, the festival is organised by a partners’ consortium, VIERNULVIER and Miramiro, in collaboration with CAMPO, KOPERGIETERY, Circuscentrum and Cultuurcentrum Evergem. The proposed theme of the clown and clowning, allowed space for exploration and (re)discovery, through contemporary renditions of a classic performative figure. With a curation philosophy focused on showcasing Flemish and Belgian circus art, peppered with occasional French productions and artists from the UK, Sweden, Switzerland and Israel, the festival presented an opportunity to grasp the ethos of recent art produced in this region.

The curatorial intention in programming is what defines a festival, and, among others, directs interest, opens dialogue, and sparks debate. This year, SMELLS LIKE CIRCUS made an interesting proposition, which elevated “the clown” from a mere figure to experience, discourse, presence, and space. What could be clowning today? What is the powerful attraction beyond the clown cliches to reveal unpleasant truths or provoke the norms?

In most ancient societies and cultures, the role of clowns is renowned for its capacity to create a catharsis, a sort of release of burdens, transforming through dissolving the fears and inadequacies of the self. Nowadays, in Western culture, they run the risk of being misunderstood as old-fashioned figures exploited by capitalistic frames. But if you look in detail you can still see some of them around you, with their madness and inspiring truth, beyond time, still pushing. You can avoid them, not understand them, or embrace the weirdness of their expressive self.

From canvas on which social and political issues are projected, or a persona made to voice critique, veiled in satire, the SMELLS LIKE CIRCUS clown is given a new approach, a disembodied, or rather ‘collectively-bodied’ presence, which journeys, with each performance, through different levels of articulation. What is being articulated, ranges from suggestions of emergent relationships with objects to ambivalent and queer restaging of classics to recalibrations of intuition and non-normative performative gestures. In it all, the audience navigates equally rich and ambivalent roles - as witnesses, decoders, and negotiators.

The genre-specific markers of circus and clown are being pushed to the outer edges of recognisability, with an illuminating offer - that, perhaps, clowning is not about what’s being recognised as clowning, but more importantly about the liminal space between recognition and a type of existential unease, which is so defining of contemporary conditions.

Futurist clowns in technicolour mutant masks: Clownscape like a landscape by Micha Goldberg

Each day of the festival, Micha Goldberg and his group of performers – Rosmary Velasquez, Giulia Piana, Giulia Bonfiglio, Pierre Patrice Kasses and Castélie Yalombo–delivered actions before and after the shows hosted in the various locations. Their actions emerged from the residency that the group did during the festival on the links between clown and queer aesthetics, creating a disturbing colourful presence and interacting with the audience.

Together with Geert Belpaeme, host of the morning talk Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast, in the antithesis that traditionally sees the august clown pitted against the icy figure of the white man, Goldberg was able to fully represent the more extroverted, curious and interactive character of the August. His experimental exaggerated attitude found its expression in the ongoing project of Micha's Amateur Theater Group, taking the steps from the previous happenings with the Ne Mosquito pas happenings.

Based on his spontaneous attraction to research through improvisation and with a glimpse of thoughts influenced by the book Ugly Feelings by the American cultural theorist, literary critic, and feminist scholar Sianne Ngai, the group's actions were often active for more than two hours straight. They took place in the front windows of VierNulVier cafe or invaded it, once surprising Miramiro's hall, displacing the passing public, who were spontaneously involved in an involuntary confrontation.

Who are they? A group of performers in technicolour mutant masks, far from dressing traditionally, totally at ease in staring at the world around them. They drip brightly coloured vaseline in stark contrast to their fixed expressions, stunned into an eerie yet impenetrable laughter. The alienating effect of seeing a group of futurist clowns in an experimental theatrical setting reminds you of how art should provoke, to strike the living wandering in search of meaning, to hit the context around you, to belong, to be free, no matter who you are. To taste, touch, see, hear and discover what is going on, even if you do not like it, contains a sort of relief. Renouncing rational analysis, we switch to a mode of absorption.

The uncanny flirting with discomfort: A Crock of Bull at the Crack of Dawn by Rachid Laachir

Rachid Laarchir is a Belgian playwright, performer, scenographer and costume designer fascinated by the exploration of metamorphosis. He speaks his own language, covering a spectrum of expressed variety, intersecting ambient design and audiovisual solutions.

Laachir’s solo performance takes place "in a space within a space"—an atmospheric tent-like interior, draped in soft, dark fabrics and installed on the stage of a black box theatre. To access the performance space, one enters and exits at the same time—the audience exits the normative, frontal setup of the theatre, the comfort of cushioned chairs and clear escape routes and enters a circular setup, where it soon becomes clear that the performance space surrounds the audience seating. This early spatial negotiation announces the mood of the performance–sat in a circle delineated by a strip of white marley dance floor, a sense of being contained is tangible. Indeed, Laachir takes the place, appropriates it, redesigns its boundaries, and clearly inverts the classic tent orientation—the audience occupies the ring.

The performance is a cacophony of episodes, instalments, and scenes populated by different characters embodied by Laachir. He enters and exits the circular stage, his presence interrupting the otherwise pitch-black moments of waiting for the new character. After each period of darkness, at a new “crack of dawn,” a new character enters the scene.

Laachir’s personas seem trapped in a serial choreography of loneliness, abjection, and confusion they appear to mistake for purpose. Sourced in normative humour (gagging, burping, urinating, a diarrhoea attack, sexual innuendos), the scenes subvert their own premise and challenge the social contract on which humour rests.

These disturbed and disturbing figures are silent and non-engaging, parading and desperately wanting to seduce the audience, while simultaneously alienating them. In an early scene of the show, a character peels and eats a mango – juice dripping between his fingers, and from the corners of his mouth, loudly gnawing on the pulp; pleasure soon turns into pain, as he starts belching, gagging, and burping. This scene is a masterful enactment of the shape of empathy and connection, and the power of presence – the audience responds as expected: silently drools at the pleasurable act, and neatly follows suit and expresses disgust at the belching scene, the response peppered with laughter.

What is the “crock of bull” with which we are all presented, at this endlessly re-enacted “crack of dawn”? Laachir’s clowning is a play with the boundaries of what it means to operate as a human, to indulge, to find humour in darkness, to drool and desire, to reject, and to (dis)connect. One of his darker characters is trying to sell us a bone—the sales pitch nevertheless fails, as it is spoken in gibberish language. Elegantly, without understanding, together and alone, at the crack of dawn, we laugh.

The subtlety of a new ethics of relation: DOS by Delagado Fuchs

If Rachid Laachir’s solo performance flirts with plurality, yet undeniably evokes a type of solitude often attributed to the clown, Delgado Fuchs’ DOS stages togetherness, on deeply corporeal premises.

The Swiss collective formed by the choreographers and dancers Nadine Fuchs and Marco Delgado, for this piece, sees Delgado in symbiosis with the dance and circus artist Valentin Pythoud, a gentle, massive, muscular presence embodying the essence of a hand-to-hand base. The performers mix mild and wild temperaments, morphing from the seriousness of their repetitive micro-movement gestures to an exquisite laughing absurdity. This dance piece uses the sensitivity of intuitive images taken from an extraordinary quality of almost animal complicity, sensitive partnership, realising a specific equity between two very unalike types of bodies.

Non-verbal, yet largely defined sonically by humming and sound effects produced by the two figures on stage, DOS explores the possibilities of human connection, where the body is an expansive contact zone. Physicality and material presence seamlessly overlap metaphors and poetics of connection. For the two humans in DOS, to be is to be here, to hold, to accompany, to witness, to lift, to mirror, to experience one another.

Their antics are rooted in universals of relation—romance, brotherly love, competition—blending aesthetics of athleticism with subtle nods to slapstick comedy. Clowning in DOS takes the form of deconstructed self-awareness, as the two characters poke fun at their seriousness.

Bodily markers of strength and an off-beat performance vocabulary that subverts them, functions to destabilise the age-old hierarchies that place fragility, vulnerability, and tenderness in opposition to strength, tenacity, and vitality. DOS embraces duality, and critically unmasks it, using clowning as a method to reveal, to bring forth, yet without falling prey to moralistic positions.

In broader strokes, DOS can be seen as staging ethics of relation predicated on recognition and support, meaningful engagement, and respect. The acrobatic language inserted in the performance is a conduit of this ethics, an affirmation of matter over metaphor, specially referred to relations. In this, DOS retains an almost historical quality of clowning - the replication of patterns and structures of humanity, restaged in critical yet comical tones, with the effect of raising questions on their legitimacy, endurance, and potential for change.

Potentiality and the overall speculative quality of movement, employ the human body, in perhaps a critique of anthropocentrism, of an all-too-human history that fetishised the body as the measure of all things. The gentle humming and vocal effects played by the artists articulate a different voice, an alternative match between living as humans in our bodies while simultaneously living inside our stories. The trick, DOS seems to propose, is never to stop reimagining these stories of love, friendship, gender, identity, and humanity.

Cie Sacekripa, Vu Vue @ Alexis Doré

Aesthetic qualities of mundanity and boredom: Vu/Vue by Sacékripa

Whilst contemporary clowning may be expected to have a dark or heavy underlying message, in Vu/Vue by the French circus company Sacékripa, we are presented with a type of 'involuntary clowning”, born out of comical and theatrical constructions. A solo piece, alternatingly performed by its creator Étienne Manceau who created it in 2012, and since 2022 adapted for women and performed by Amélie Venisse, Vu Vue is object theatre and minimal circus, which champions the aesthetic and performative values in explorations of boredom, routines, and the little daily things.

The minimal universe has clear boundaries drawn on the stage floor, imaginary walls to a small room, in which the artist sits at a miniature desk and progressively deals with the ennui of a usual day. Only the day is not usual at all, the objects are not as predictable as we think, and a quotidian affair such as making a cup of tea expands into a bubble of unexpected excitement.

The scale of the scene, the small size of the objects and the detailed movements of the artists do their magic and paradoxically arrest attention for the duration of the performance. The mastery of the piece resides, among others, in the understated humour, a type of comedy that, without trying too much, manages to simultaneously delight and compliment its audience. Targeted at younger audiences, Vu Vue does not take its audience for granted and gently negotiates participatory moments with the public.

The cynical, morose clown proves nevertheless a (secretly) jovial character, who finds the playful qualities in daily objects. What, if not joy, can drive an otherwise surly character to adorably tease his audience, and find whimsical approaches to the inevitably mundane? Slow and surly, the cranky clown embraces mundanity and boredom, almost with didactic qualities — a reminder to seize the moment, for what appears dull and dreary may be full of endless possibilities.

Geert Belpaeme, Please (don’t) Let me be (Mis)understood © Frank Emmers and Anaïs Chabeur

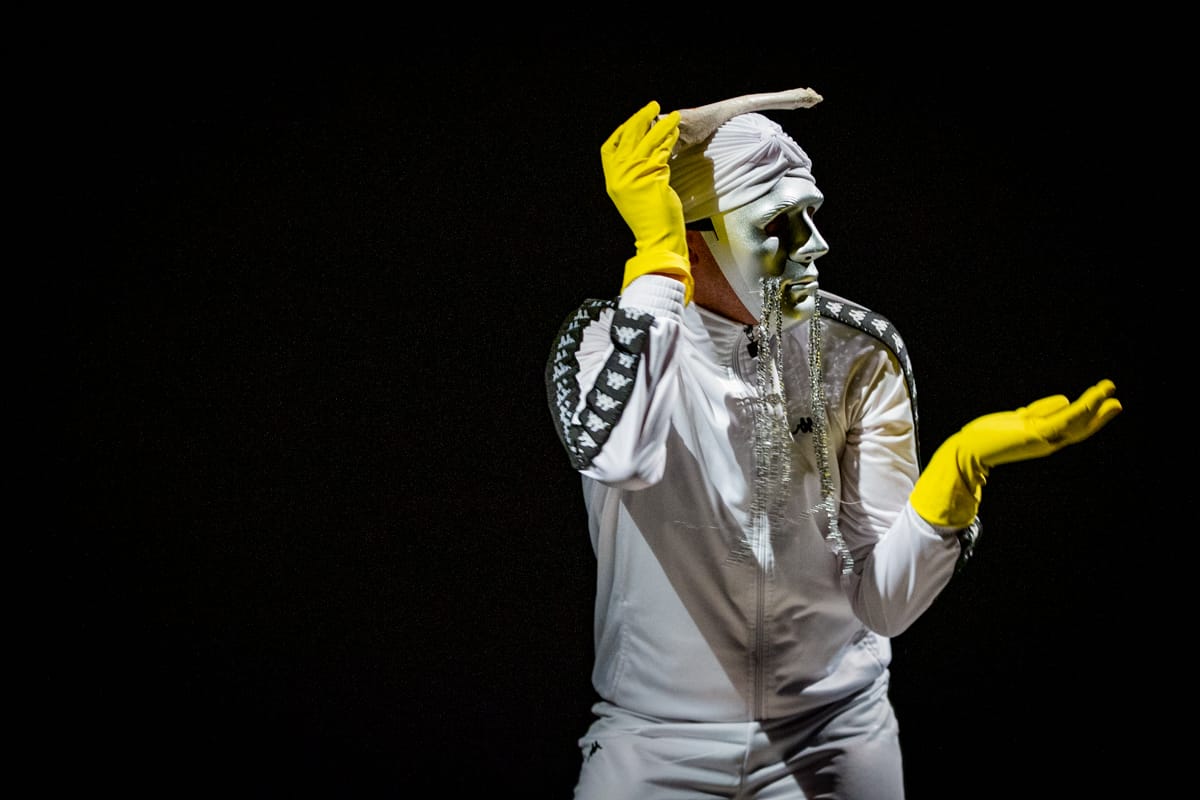

Speculative and deconstructive clowning: Please (don’t) Let me be (Mis)understood by Geert Belpaeme

Theatre, dance, and clowning are brought together in Please (don’t) Let me be (Mis)understood—a performance that uncompromisingly and unapologetically stages the figure of the clown, against its history of normative, at times derogatory use. A journey of humanity itself is rendered in the performance, which follows the inquisitive and critical takes, specific to the oeuvre of the Belgian performance artist Geert Belpaeme, creator and performer of this performance.

If humanity progressed from darkness and confusion to order and knowledge (or so modernity likes to tell the story), Belpaeme’s dramaturgy journeys towards deconstruction, chaos, misunderstanding — and the consequent plea for being understood, announced in the title. Clowns tell this contradictory tale of what it means and what it looks like to be human, from a post-human perspective.

The clown is revisited here as the figure culturally and historically tasked with performing discrepant experiences of what it means to be human; the passion, rage, the push and pull of curiosity and desire. Belpaeme’s clowning goes beyond human-centred concerns and addresses more-than-human relationships and interconnections. In aesthetics and critical construction, Please (Don’t) Let me be (Mis)understood showcases the open-ended potential of the art form, the speculative capacity and agility of the discipline to attune itself to current problems, with care and concern for the future.